Reviewed by Grant McCreary on August 6th, 2014.

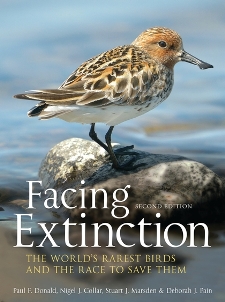

A charge often leveled at birders is that many of us do not care about conservation. I take issue with that. Yes, it’s true that, in general, birders could do more, but we already do much for conservation. If you need any proof of that, just check out the ABA Birder’s Guide to Conservation and Community. But the thing that bothers me most about that claim is that I don’t see how you can be a birder and not care about conservation. Now, I don’t like it when people try to tell you how you should get enjoyment from birding; everyone is different. But it’s only logical that if we don’t do something for birds, many of the birds we enjoy watching could disappear. And even for those who just care about ticking off life birds, knowing about conservation status can help you prioritize species to look for. (Want to add Spoon-billed Sandpiper to your list? Better hurry.) Knowing about rarity in birds is in the self-interest of birders. And there is absolutely no better introduction to this subject than Facing Extinction: The World’s Rarest Birds and the Race to Save Them.

Facing Extinction is a detailed look into the nature of rarity: how and why birds become rare, with particular attention paid to island species, and how they can be saved. The questions the authors seek to answer are:

Why are some species rare and others not? Where do rare species occur? What can be done to prevent rare species from slipping over the brink to extinction? And where will rarity occur in the future?

Each of these topics is covered in-depth in its own chapter. They can get pretty complicated, but even a layperson like myself can understand it. The numerous graphs and tables help to understand the numbers and statistics presented. But don’t let the technical nature of the discussion dissuade you from reading these general chapters, I found them full of surprises. For instance, one of the traits of island birds that predispose them to endangerment is flightlessness. This condition evolves in island species without predation pressure because flight, along with the physiological support required, takes a lot of energy. This happens across many different types of birds, many of which we’re familiar with, such as the Dodo and Flightless Cormorant. But I had no idea how quickly a species can lose the ability to fly. Apparently it can happen even before speciation, as there are both flying and flightless subspecies of the White-throated Rail!

One of the best ways to learn is by example, so Facing Extinction includes 20 case studies – chapters on particular birds that best exemplify the topic at hand. Here’s the complete list:

-

The distribution and causes of rarity

- Sociable Lapwing

- Spoon-billed Sandpiper

- Brazilian Merganser

- Royal Cinclodes

- Bengal Florican

- Liben Lark

- Yellow-crested Cockatoo

-

Rarity and extinction on islands

- Stephens Island Wren

- Tristan Albatross

- Raso Lark

- Po’ouli

-

Saving the world’s rarest birds

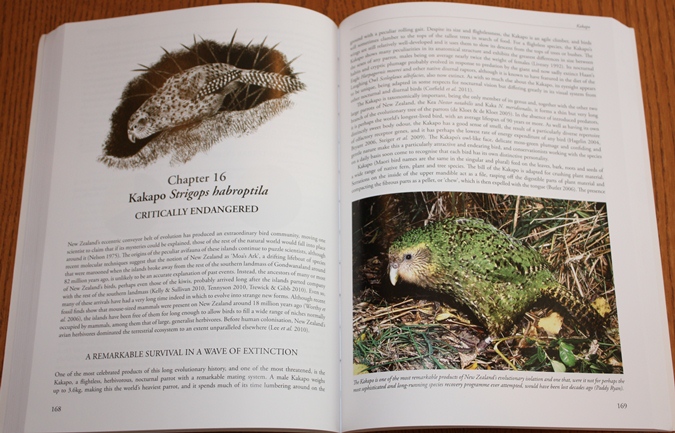

- Kakapo

- Asian vultures

- Philippine Eagle

- Alagoas Curassow

- Spix’s Macaw

- Madagascar Pochard

-

The lost and the found

- Gurney’s Pitta

- Forest Owlet

- Slender-billed Curlew and Eskimo Curlew

These case studies are very detailed. Some stories that (I thought) I knew well, like the Kakapo and Asian vultures, I still learned a great deal. The case studies not only describe the current status of the species, what is being done to save them, and their prognosis, but also the history of how they became rare and of past conservation attempts. The efforts that have gone into saving the Kakapo, for example, are enormous. And the account of the vultures reads like a medical mystery. By the time I was first aware of the issue, the cause behind the decline was already well-known. I had no idea that it was such a mystery for several years, or that the population collapse happened so quickly that there was barely enough time to save these previously abundant birds from extinction.

I find books like Facing Extinction to be fascinating, and this one is no exception. However, they can be extremely frustrating – heartbreaking, even – to read. It’s hard not to be pessimistic when reading about all these birds in trouble. That’s especially so when you consider the concept of ‘extinction debt’, a truly frightening idea that I learned about here. This is the sometimes “considerable time-lag between the event that precipitates a species’ extinction and the death of the last bird.” The idea is that a species can hang on in a degraded, fragmented environment for a little while (which could easily be over a century), but it is still essentially doomed to extinction. It seems that we’re fighting, as Agent Smith told Neo, inevitability.

But the authors assure us that not all is doom and gloom. They tell of several success stories, like the Kakapo. Of particular hope is the fact that many species thought to be extinct have been rediscovered, some in much greater numbers than thought possible. If there’s one message that Facing Extinction gives, it’s that:

The messages that these discoveries and in particular the rediscoveries hold for us are all positive, but with a distinct catch. They are telling us that we still have a chance, that the planet is still that bit richer in resources than perhaps we had imagined. But the most crucial lesson these birds are teaching us is not to allow ourselves to assume that we can afford to relax: this chance to save them will be the last.

Recommendation

I’ve read many books about endangered birds, and Facing Extinction: The World’s Rarest Birds and the Race to Save Them is the best that I’ve seen at explaining how and why birds become rare. And it’s filled with interesting stories, from mysteries to exciting discoveries, about rare birds. This book is essential to anyone working in conservation, and an excellent introduction to rarity in birds for anyone who cares about them.

Disclosure: I get a small commission for purchases made through links in this post.

Buy from NHBS

(based in the U.K.)

Disclosure: The item reviewed here was a complementary review copy provided by the publisher. But the opinion expressed here is my own, it has not been influenced in any way.

Comment