Reviewed by Grant McCreary on April 2nd, 2021.

When I think of vultures, I think of the skies and roadside here in the Southeast United States. I see one of the two New World Vulture species that occur here, and across most of the US, just about every time I get in a car. Or, if I’m thinking beyond the local, “vulture” brings to mind scenes from wildlife documentaries of gangs of birds devouring carcasses on the African plains. These would be Old World Vultures, which are not related to their New World counterparts, though there are many similarities due to the process of convergent evolution. What I do not think about, however, is Spain. If the same could be said for you, reading A Vulture Landscape: Twelve Months in Extremadura will correct that.

Over the course of twelve relatively short chapters, corresponding to the months of the year, Ian Parsons introduces the reader to the vultures of Extremadura, Spain. He accomplishes this by bringing the reader along with him, so to speak, as he birds the countryside looking for vultures. The most common vulture here is the Griffon Vulture, a year-round resident of Extremadura. The Black Vulture is also regularly encountered. Note that this is not the same species as the Black Vulture of the New World, but rather what has been officially renamed as the Cinereous Vulture, though Parsons prefers to continue using the older, “properly descriptive” name. Playing a much smaller role in this story is the Egyptian Vulture, a summer breeder. Rounding out the vultures of Extremadura are the Bearded, a rare visitor, and Rüppell’s, an even more infrequent vagrant from Africa.

Parsons takes us to nests, roosting sites, and, of course, to vulture feeding frenzies. Along the way, we learn a great deal about these birds. The most interesting thing I learned was how they find food. Unlike Turkey Vultures, Old World vultures do not have a keen sense of smell, so they find food by sight. But even though they have good eyesight and can travel great distances effortlessly, it’s not immediately clear how a large number of vultures can congregate so quickly at carcasses. Parsons shows us how they do this by following vultures from their roost site in the morning. The birds quickly scatter, becoming distant spots in the sky. But this is anything but random. When one bird spots food, it starts to descend. Parsons observes a chain reaction:

As soon as that first Griffon Vulture changed course…a ripple of interest spread through the vultures spaced out across the sky. Those that could see the first bird would have reacted to its change in behaviour, and that reaction would have been reacted to by the birds that could see those birds, and so on. As soon as the first bird stared to lose height, the others would have immediately followed, which, in turn, would have been followed by the next birds in the chain of visibility. The sky is suddenly full of these magnificent birds coming from everywhere. A few minutes ago, I couldn’t see one; now I can see dozens and dozens.

Parsons shares with us many aspects of vulture biology, their adaptations, and their daily lives. But it’s much more than just cool facts about these birds. He also tells us about how vultures have influenced human culture, and, conversely, how humans have impacted vultures. Some aspects of the latter have benefited vultures, such as the dead livestock left out for them on the Spanish plains. Unfortunately, though, humans have done much more harm than good for them – 11 out of 16 Old World vultures are endangered, many of them critically.

Although the main focus here is on vultures, the author does not ignore other birds; we meet plenty of them along the way. We also get a feel for the land as a whole. Parson’s affection for this landscape permeates every page. While this environment of open, sometimes harsh, spaces may not at first glance seem all that interesting, it just requires a closer look, as the author tells us: “it is easy to think of [the plains] as empty landscapes, devoid of interest. But the opposite is true; they are packed full of life, continuously busy with the everyday drama of survival.” This book gives an excellent taste of the birds and birding in Extremadura.

It’s not easy to make first person accounts, like the ones A Vulture Landscape are built around, not only informative but entertaining as well, but Parsons handles it splendidly. His descriptions are evocative, making it easy for the reader to place themselves in the scene, and the writing as a whole is engaging, making this book a pleasure to read. I, for one, was drawn in and didn’t want to stop reading.

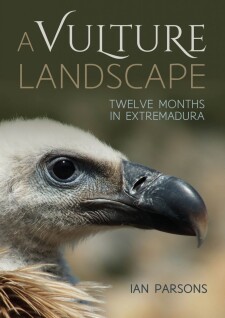

Books such as this do not usually have many illustrations. This is the exception, it has many photographs of the birds and landscape of Extremadura. Not being very familiar with either, I was very grateful for their inclusion.

Recommendation

As the title indicates, A Vulture Landscape: Twelve Months in Extremadura does deal with a specific group of birds in a very specific region. But even if you have no especial interest in vultures or have never considered birding in Extremadura, this book is still worth reading. Parson’s passion for vultures is contagious, you can’t help but gain an appreciation for these often misunderstood birds. And, if you’re like me, you will find yourself wishing to be vulture gazing in Extremadura.

Disclosure: I get a small commission for purchases made through links in this post.

Buy from NHBS

(based in the U.K.)

Disclosure: The item reviewed here was a complementary review copy provided by the publisher. But the opinion expressed here is my own, it has not been influenced in any way.

Comment