Reviewed by Grant McCreary on January 28th, 2011.

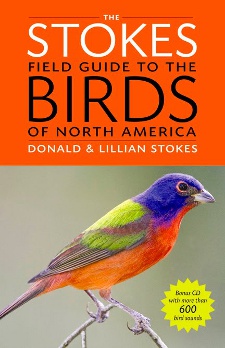

In my initial look at the Stokes guide, I expressed a very favorable opinion of it. After spending some more time with the guide, my thoughts haven’t changed much. I would highly recommend it, though not as a field guide. What do I mean? Read on…

The Stokes Field Guide to the Birds of North America covers 854 species, all of which are on the official ABA Checklist. The taxonomy is relatively up-to-date, even including the “new” Pacific Wren. It does not, however, give Mexican Whip-poor-will its own account, though it does cover the differences between it and its former conspecific nicely.

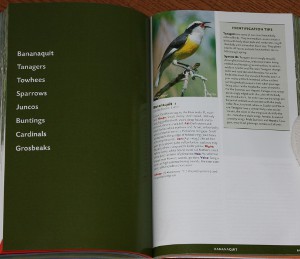

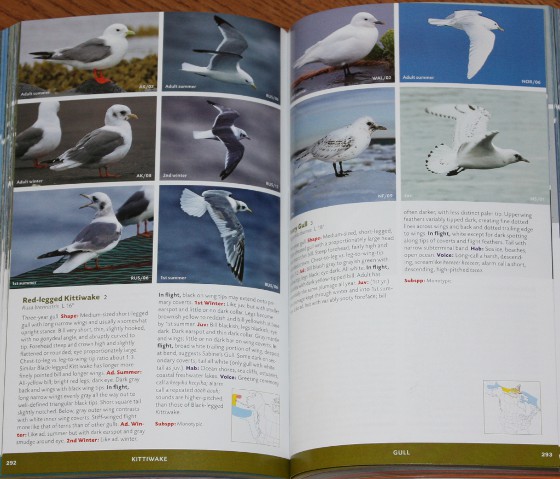

Each account occupies one half to four pages, with an average of about one. I like the layout, which presents the photographs first, at the top of the page, making it easier to compare species. The lack of margins between the photos and page edges allows the photos to be larger, and gives the guide an attractive look.

Photographs

In a nutshell, they are good, and there are a lot of them. The quality of most is good to superb, though there are a very few that I would consider sub-par. But even then, they were chosen for their instructive value rather than beauty. (Though there had to have been a better Black Phoebe profile shot.) The pictures are also larger than those in most photographic guides.

Each photo is captioned with not only the bird’s age, sex, season, and subspecies when known, but also the location and month it was taken. This is a very useful feature, and one that I wish all photo-based identification guides would emulate.

But to me, the best thing about the photos is the sheer number of them. One of the main advantages of paintings-based field guides over photographic ones is the amount of variation they can show. Just look at the Sibley or Collins guides and the amazing number of illustrations per species they provide. Photo field guides have never attempted anything close, until the Stokes. On average, the Stokes guide has four photos per species. This still doesn’t match Sibley, but is much higher than any other photo field guide I’m aware of.

Species Accounts

Besides the species’ name, of course, each account includes:

- ABA Code – number (1-6) next to the name indicates rarity

- Size – length of the bird, in inches only

- Shape

- Plumage – broken down by age, gender, and season

- Flight – plumage, shape, and behavioral clues

- Habitat

- Voice

- Subspecies – number in North America, names, brief description, and range

- Hybrids – list of species with which it’s known to hybridize

I’m undecided whether the ABA code or terms such as “common” or “scare and local” are a better method to indicate how likely one is to find a bird. Regardless, I’m happy to see the codes included here; a surprising number of field guides don’t provide anything of the sort.

The shape and plumage descriptions are quite extensive for a modern field guide. The emphasis put on shape is especially great to see, as it is often overlooked. But, of course, there’s bound to be a few field marks that aren’t mentioned. Many guides call attention to definitive characteristics in some way, whether via arrows pointing to field marks or bolded text. Whatever the method, a field guide needs to succinctly highlight the most important identification information. That was not done here, however, and it often leads to long, intimidating lists of things to look for.

My favorite part of the text is the treatment of subspecies. The Stokes follow Peter Pyle’s classification of subspecies and summarize the ranges and descriptions from his excellent, two-part Identification Guide to North American Birds. I’ve long been looking for a single, concise source for this information. This alone has earned the Stokes field guide a spot among the primary reference material that I keep close by.

As birders quickly learn, behavioral traits can be as important for identification as plumage, shape, or anything else. Appropriately, some key behaviors are noted in the Stokes guide, but are buried in the plumage descriptions where they may not be noticed. For instance, the Palm Warbler account does state that they pump their tails, but it’s mentioned in the Adult Summer section. Of course, they pump their tails just as much in winter! A separate section dedicated to behavior would have been much more preferable.

The range maps have distinct colors for permanent, summer, winter, and migratory ranges. They also use dotted lines of the appropriate color to indicate areas of rare occurrence. The maps were created by Paul Lehman, so they’ll be very similar to most of the other recent field guides, which also use his data. The area shown in the maps is scaled nicely depending on the bird’s range.

The only problem is that the maps themselves are all of the same, very small, size. I have good close vision, but I have to hold the book uncomfortably close to make out some details. The dotted lines can be especially hard to see. It would have been nice if the maps could have been reproduced a bit larger. Some accounts use every bit of their allotted space, so their maps could not have been any bigger. That’s understandable. But many leave a great deal of blank space, making their maps appear ridiculously tiny. Granted, having some maps larger than others would be inconsistent, but it would be more reader-friendly. At the very least, darker colors could have been used.

Other Features

The introduction is very short, consisting solely of the obligatory “how to use this guide” and a series of photographs labeled with the parts of the bird. A “Quick Alphabetical Index” is printed on the front inside cover flap. This is a handy feature that should be standard on all field guides. There is also a bonus CD with 150 tracks, in MP3 format, sampled from the Stokes bird songs CD set

Issues

This may or may not be a problem, depending on your needs. At 5.5 x 8.5 inches (14 x 21.5 cm), this is one of the larger field guides, though it’s not all that much larger than the National Geographic guide. But when you combine that with its thickness and weight (it’s heavier than the “big” Sibley!), it becomes unwieldy to use in the field. It would fit only in the largest pocket or, preferably, a bag or backpack.

Here are a few additional issues that I had with this guide:

Related families are grouped together with color-coded lower page borders. This helps navigation, and isn’t a problem. But each of these sections has an introduction page that simply lists the families covered. This is a colossal waste of space. Some boxes with general information and identification tips are included for some families, but these are interspersed throughout the accounts. It would seem to make more sense to move these to the mostly-blank intro pages. This would either allow a few pages to be trimmed from this thick book, or more photos and text to be included.

Related families are grouped together with color-coded lower page borders. This helps navigation, and isn’t a problem. But each of these sections has an introduction page that simply lists the families covered. This is a colossal waste of space. Some boxes with general information and identification tips are included for some families, but these are interspersed throughout the accounts. It would seem to make more sense to move these to the mostly-blank intro pages. This would either allow a few pages to be trimmed from this thick book, or more photos and text to be included.- As previously mentioned, one of the guide’s main strengths is the amount of variation shown. This makes it all the more disappointing when some important plumages are not illustrated. Immature Saw-whet and Boreal Owls, for example, are conspicuously absent.

- Wingspan measurements are not given for any bird.

- Measurements are only given in inches. It would be nice if the metric equivalent was also included.

- The order of species could have been further tweaked to give a better comparison of similar birds. The swallows, for instance, could have been rearranged to have Cliff and Cave Swallows, and Northern Rough-winged and Bank on facing pages.

The only outright error I’ve noticed is that the Red Knot is listed as monotypic, when there are three subspecies that breed in North America (and six total). Even though other sources (such as Handbook of the Birds of the World) consider the Red Knot as a complex of five or six subspecies, Pyle does not. Since the Stokes guide uses Pyle as its source for subspecies information, it is thus correct in listing the knot as monotypic.

Recommendation

The Stokes Field Guide to the Birds of North America contains an extensive collection of photographs and useful information not included in other field guides. Even if you don’t plan on using it in the field, it makes an ideal compact reference to keep in your car or close at hand at home.

Disclosure: I get a small commission for purchases made through links in this post.

Disclosure: The item reviewed here was a complementary review copy provided by the publisher. But the opinion expressed here is my own, it has not been influenced in any way.

Thank you so much for your review. We’re glad you like the layout, extensive photographs, and the fact we are the only guide to include all the subspecies information.

Your readers might be interested to know why we chose to do certain things in the way that we did.

We cover 854 species, 100 more rare ABA checklist species than almost all other field guides, including Sibley and Peterson. There are over 3,400 photos in an uncluttered layout clearly showing each bird. That’s over 1000 more photos than any other national photo guide. We chose from over 100,000 photos and the photographs we included have been praised for their outstanding quality and high reproduction standard. The photos are from168 of the world’s top bird photographers.

Our philosophy was to use more photos and text for difficult-to-identify species or when warranted. For example, for Red-tailed Hawk there are 23 photos and 4 pages of text. The Black Phoebe photo, which you mention, nicely shows the profile shape and was taken by Brian Small, one of the country’s leading bird photographers. In a field guide of this magnitude, it was occasionally hard to locate a perfect photo because the species was rare, the plumage infrequently photographed, or the bird was difficult to photograph.

As with everything in this new guide, we paid a great deal of attention to detail when writing the text. You have suggested that the text fails in some cases to highlight the most important clues with either bolding of the text and/or arrows on the photos.

Use of Arrows

Let’s start with the use of arrows. We initially considered putting arrows on the photos but decided not to for many key reasons. One is that it clutters up the visual strength of the birds themselves and can come between the reader and the beauty of the birds.

Also, it is our belief that arrows tend to limit the extent to which people look at the images in field guides. They often just look at where arrows point and then stop looking. We wanted to encourage looking at the whole bird and continuing to study it to see more features.

In addition, arrows in other guides usually just point to color and never deal with shape; but since our approach gives equal weight to shape, we would have needed two types of arrows to distinguish those pointing to color clues and those pointing to shape clues. This quickly becomes cumbersome.

Also, in guides that use arrows, such as Sibley, the arrow may point to a characteristic on one image (showing a particular age or sex) and then not on the other images which also contain the key characteristic previously noted. This then becomes confusing. For example, on Sibley’s Long-billed Curlew, p. 175, he has two arrows on the juvenile bird pointing out the pale gray legs and the plain crown; but these clues, which are clearly important to the adult as well, are not shown on the adult. Does this mean that they are key to identifying just the juvenile and not the adult? You can see how confusing this could be to a beginner. If, for consistency and clarity, he had repeated all arrows for each picture, then this begins to make the birds look like pin cushions and distracts from the beauty of the illustration.

Because of all of these reasons, we left text and arrows off of the photographs.

Bold Text

Next is your comment that the text does not highlight the most important clues by bolding those clues. First of all, note that neither Sibley or National Geographic bolds clues. In general, the most important clues in our guide, those that are needed by beginning and intermediate bird watchers, are always at the beginning. Later clues are for the more advanced birders who understand particular and more subtle problems that can arise between a species and those that are similar to it or for aging and sexing or subspecies distinctions. We have never given just a laundry list of bird traits; every identification clue is there for a reason and the more advanced you get, the more useful you will find our text.

For example, Our Northern Mockingbird text for adult states:

Gray above; whitish below; 2 white wingbars; white base to primaries creates a patch on edge of folded wing. Indistinct gray eyeline; yellowish eye.

The whole first sentence is key and would need to be bolded. The second two clues help distinguish it from Bahama Mockingbirds and help tell its age. For the more advanced birder, this should also be bolded. It is our belief that all clues mentioned in this guide are key clues, depending on how deeply you delve into the identification problems with a given species. In addition, bolding text, like arrows on birds, often limits what the reader absorbs, and in the long run works against careful and accurate identifications.

For these reasons, we did not bold text.

Intimidating Lists of Clues

You have also stated that in our clues we have often given long intimidating lists of things to look for. There are certainly some species where you only need to look at a few things to identify the bird, such as Northern Cardinal. But many other species and groups of species require looking at many more details to accurately identify them, such as Empidonax flycatchers, many sparrows, and many female and immature warblers. These birds may require a lot of clues, but no clue has been listed superfluously. Treating these tough species with any shorter accounts would be a disservice to birders who are actually trying to identify them, by either suggesting that their identification is easier than it really is or simply not giving the birder enough to clearly distinguish the species from other similar species.

Other Text Points

Something that we also did with our text was to create parallel accounts for all species within a group. By this we mean that, for example with the gulls, each description of plumage starts with the bill, then the eye and legs; after that we proceed to the back and wings. This is subtle, but can help the reader compare accounts for related species and more quickly retrieve information in the long run.

You will find that most other field guides have highly fragmented text, with multiple captions and phrases scattered about the page. This make it very hard to be sure you have read all the clues or read them in an order that leads you to a helpful conclusion. Our text is unified and some of the most readable of any field guide.

Use of Space

You commented that the heading pages for groups of birds are a waste of space and that descriptions of the groups of birds could have gone there. It is a common design flaw to try to pack every page with text or pictures. Good design always leaves breathing room for the reader; places where they can take a breath and have some mental and physical space between areas of intense text and photos. In addition, we have over 45 extensive introductory sections to bird groups and this would add another 20-30 pages.

Correction

Finally, you state that there is an “outright error” in the number of subspecies listed for the Red Knot; but at the same time you have acknowledged that we followed Peter Pyle for our subspecies. If you read Pyle on Red Knot, you will see that he treats it as monotypic for North America. Could you please correct this part of your review.

Size of Guide

As to the size of the guide and your claim it is not a field guide, we believe that field guides should be characterized as field guides based on the information they contain, not their size.

Our guide covers all the field clues and has, in most cases, more extensive information on bird field identification than any of the other North American books with the word field guide on their cover.

If one were going to judge a field guide solely on weight and size, then there would be as many different lists of what is and is not a field guide as there are people, since it is all based on personal opinion.

Many people do carry The Stokes Field Guide to the Birds of North America in the field. We recommend the Pajaro Field Bag, for the waist, which nicely fits our, and other field guides. Other people just carry our guide in their car, or in a back pack.

Once again, thank you for your review.

Don and Lillian Stokes

Wow, thanks for the feedback.

Arrows – I agree with your decision to forgo their use. I’m a big fan of annotated arrows in painting-based guides, like those in Sibley, Collins, and the regional NatGeo’s. But they work there because of the white space afforded by the medium. Trying the same thing with photos would be too cluttered and very unattractive. In regard to the Sibley arrows, the fact that common field marks are pointed out on just one image never confused me, though I must admit that I have, at times, overlooked some because of this. But I learned to carefully check out every image and read every caption.

Bold text – I don’t do well with long lists of field marks, but I guess this is more of a personal preference (or failing). When I’m studying just a single, or few, birds for a specific reason, I don’t mind so much. But if I’m studying in general, or many birds for a trip, I like to be able to get the most important information at a glance. I don’t necessarily want to read through every detail at that time (though I would be glad to have it for later, if needed), I just like to be able to quickly see what I need to look for. I think that’s the main reason I like annotated arrows so much. This is just what I look for personally, I’d love to hear what others think.

Space – I agree about the importance of breathing room, but I don’t think moving the family info boxes to the intro pages would have made it too busy. For most of the family groupings, anyway. There would be some where everything may not fit on the single page, but even including some of them should allow some pages to be trimmed rather than added.

Red Knot – I don’t have the Pyle guides (they’ve been on my wishlist for a while), so I based my comment on another source (wikipedia). I also checked HBW, and they recognize 5 subspecies, with 3 breeding in NA. But you’re right, since you’re based on Pyle, this should not be considered an error if they differ. But does Pyle consider the entire species monotypic globally? If not, then the Stokes guide should instead indicate (1) instead of “monotypic”. If he does, any idea why? And (this is off topic) what does that mean for conservation efforts aimed at the rufa subspecies (if it is one) that migrates along the eastern coast of the US? Regardless, let me know and I’ll correct my review.

Size – I didn’t mean to imply that it wasn’t a field guide, as birders generally understand the term, but that the size and weight made it more inconvenient to carry in the field. If I had been birding when the first Sibley guide was published, I would have said the same thing, and of course I consider that a field guide as well (it, too, stays at home or in the car, I’ve only ever carried the smaller regional Sibleys in the field).

Thanks again for the comment, I very much appreciate the “behind-the-scenes look” at the rationale of some of the choices.

Grant,

Pyle considers the Red Knot monotypic throughout, so could you please correct your review. You should get his books; there you will see all of the articles and reasons behind his decisions. They are a must for any birder.

Don and Lillian Stokes

I’ve corrected the review to reflect this.

I was saving up for the last volume of HBW, but this was the last straw, I’m finally ordering the Pyle books.

I think it takes longer for me to write reviews than it should in a large part because I want them to accurately reflect my thoughts and opinions. It’s not always easy to do, and sometimes when looking back I realize that something came across that I did not intend. Such was the case with my original “Recommendation” in this review. As the Stokes point out in their comment, it could have been construed that I don’t consider this to be a field guide. That’s certainly not the case. I do think the size and weight make it prohibitive, though not impossible, to carry in the field. But it is most definitely a field guide. I’ve thus changed the wording in my recommendation to hopefully reflect this better. For the sake of transparency, this is what I originally wrote:

I see The Stokes Field Guide to the Birds of North America as a compact reference book rather than as a field guide. Its size and weight make it uncomfortable, though not impossible, to carry while birding. But the copious photographs and useful information not included in other guides make it ideal to keep in your car or close at hand at home.