Reviewed by Grant McCreary on July 30th, 2008.

In 1934, a young man named Roger Tory Peterson forever changed the way that we would look at the world around us. For it was then that his first field guide to the birds was published (for the full story, check out his biography, Birdwatcher). Peterson accomplished much during his storied life, but the five editions to his guide to the birds of Eastern and Central North America, and the three of its companion volume for the West, remain the most influential and well-known. Many generations of birders have relied upon these guides, and with the publication of this volume, the legacy will continue.

This, the first edition of the Peterson Field Guide to Birds of North America

, is a combination of the previously separate Eastern and Western regional guides. The look and feel of this guide will be immediately familiar to any users of past editions, especially the latest Eastern. However, every aspect of the book, even the art, has been enhanced and updated according to current knowledge of birds and their identification.

Layout and Size

With good reason, the overall layout is the one thing about this new edition that has not been updated. The art (or “plates”) is displayed on the right-hand pages, while the facing ones contain the species accounts and thumb-nail sized maps. Like previous editions, there is a section of large-scale maps in the back, before the index.

There have been a few changes to the species order. The order is now more strictly based on taxonomy. The swifts, for example, are no longer found with the swallows, but are placed next to the hummingbirds, according to the currently excepted taxonomy. Also, an effort was made to group all paintings of species on the same plate. Previously, the book showed some adult and immature sparrows on different pages. Now they are grouped together, as they should be. There are a few exceptions, such as the separate plates for fall warblers and overhead raptors that are still present.

Since this guide covers the entire continent, it is larger than its predecessors are, as one would expect. The trim size is significantly larger, and it is a little thicker. Among North American field guides, only the “big” Sibley is larger.

Plates

Overall, unless one knows Peterson’s art extremely well, or does a direct comparison with the regional Peterson guides, you would not be able to spot many changes to the plates. But there have in fact been many.

The most extensive changes have been in the form of digital enhancements to Peterson’s art. These are touch-ups and corrections to make the bird on the page look more like the bird in the field. Sometimes it takes the form of color corrections, such as the male American Wigeon that is now more rufous overall. Other changes add new field marks, as in the black spot at the gape of the Mottled Duck. And still others change the shape or structure of the bird, like the Least Flycatcher’s reduced primary projection. These enhancements have been artfully done, and do not stand out. They look as if they have always been part of the painting. The enhancements have indeed improved the image of every species that I’m familiar with (with one exception, as described below). And for less-familiar species, they have made them look more in-line with other sources. The one glaring exception is the Ross’s Goose, whose bill size has been increased so that it no longer looks stubby, as it should.

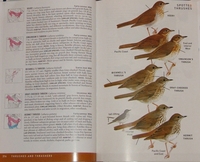

There are also some entirely new paintings, done by Michael O’Brien. Some, like the Himalayan Snowcock, are new species that have never before been included in a Peterson guide. But some previously included birds have been completely replaced by new paintings. The new paintings have been done in Peterson’s general style, and some are very tough to pick out. But unfortunately, most are obvious. They are not bad, just different, and that difference can be jarring. It is hard for me, not being an artist, to describe the difference, so I’ll show you instead. See if you can pick out the new painting on this plate of myiarchus flycatchers.

There are also some entirely new paintings, done by Michael O’Brien. Some, like the Himalayan Snowcock, are new species that have never before been included in a Peterson guide. But some previously included birds have been completely replaced by new paintings. The new paintings have been done in Peterson’s general style, and some are very tough to pick out. But unfortunately, most are obvious. They are not bad, just different, and that difference can be jarring. It is hard for me, not being an artist, to describe the difference, so I’ll show you instead. See if you can pick out the new painting on this plate of myiarchus flycatchers.

For more detailed information on which species have been added, removed, and redone, a complete list of changes is available.

One thing that has not changed is the use of arrows to point out the most salient field marks on the illustrations. This Peterson innovation is a simple and succinct way of showing birders what to look for in the field, and it has been carried over here.

Peterson’s style and plate layout are by now probably familiar to most birders, so I will just touch on a couple of points. The Peterson guides are often touted as the best guides for beginners due to their ease of use. I certainly agree with that. However, some stylistic choices actually make identification more difficult, especially for novices. One in particular stands out – some birds are not shown completely. Presumably, this was originally a compromise made in order to include every species in the limited space available. This may have been needed in the early editions of the guide, but by the time of the Eastern 5th edition, it should have been unnecessary. As an example, Peterson positions some female and immature birds behind males. Most of the time this is acceptable, however, in some cases it can conceal important field marks. For instance, the Rose-breasted Grosbeak female is positioned so that the unique pattern of white in the wings is hidden.

Perhaps even worse is that some birds, such as gulls and terns, are only shown as a close-up of the head and/or in flight. I can only imagine the frustration of a beginning birder trying to use this guide on their first trip to the beach, trying to identify a group of nonbreeding and immature terns based on the head alone (much less gulls)! Sure, it can be done, but not reliably by most birders, given the variations due to molt and individual differences. And yes, the text mentions the dark shoulder (carpal) bar that differentiates Common and Forster’s Terns, but it’s not the same as having it illustrated.

Perhaps even worse is that some birds, such as gulls and terns, are only shown as a close-up of the head and/or in flight. I can only imagine the frustration of a beginning birder trying to use this guide on their first trip to the beach, trying to identify a group of nonbreeding and immature terns based on the head alone (much less gulls)! Sure, it can be done, but not reliably by most birders, given the variations due to molt and individual differences. And yes, the text mentions the dark shoulder (carpal) bar that differentiates Common and Forster’s Terns, but it’s not the same as having it illustrated.

Peterson’s art has never looked better in a field guide. The art here may look a little better than in the latest Eastern edition, but if so, not by much. Compared to the Western guide, however, it is a revelation. The same paintings in the Western guide are dull, soft, and look out of focus (if that’s possible for paintings). But here they are vibrant, and you can see more of the fine detail. Additionally, due to the increased trim size, the paintings are reproduced larger than in the regional guides.

Species Accounts

The accounts include:

- Abundance

- Size – length in inches and centimeters

- Description – with important field marks in italics

- Voice

- Similar Species

- Habitat

The Range section included in the regional guides is no longer present. This is perfectly acceptable since it would be largely redundant due to the maps. Many more accounts now feature a Similar Species section, whereas before very few did.

Like the art, the text has also been extensively enhanced and updated. For the most part, this consists of editorial changes such as word usage. However, many new field marks and other information have been introduced. For instance, the Red Crossbill account now mentions that there are many subspecies that are differentiated by flight call, whereas this was not touched upon previously. On the other hand, some remarks have been removed. Again using the Red Crossbill as an example, the fact that the crossed mandibles are often difficult to see (which is definitely the case) is unfortunately no longer mentioned. On the balance, though, the changes have improved the accounts.

Each family gets a short introduction, which includes a quick description, their food, and worldwide range. They are mostly the same as in previous editions, except for some reason the number of species worldwide is no longer included. Large, diverse families, such as the ducks, can be broken down into one or two levels of subcategories, each with its own introduction that adds some more specific details. For instance, Geese, Swans, and Ducks -> Diving Ducks -> Eiders. Altogether, these introductions are by no means comprehensive, but they do give some important information and are worth reading.

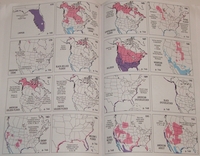

Maps

There is an entire section of large range maps in the back of the guide, and each species account includes a small thumbnail map. The maps use three colors to indicate the breeding, winter, and permanent ranges. However, more information is conveyed through the use of dotted lines to show additional areas where the species is rare or irruptive. Additionally, the large maps are annotated with supplemental information such as recent range changes, wintering areas of neotropical migrants, and migration routes.

There is an entire section of large range maps in the back of the guide, and each species account includes a small thumbnail map. The maps use three colors to indicate the breeding, winter, and permanent ranges. However, more information is conveyed through the use of dotted lines to show additional areas where the species is rare or irruptive. Additionally, the large maps are annotated with supplemental information such as recent range changes, wintering areas of neotropical migrants, and migration routes.

This same arrangement had been used in the latest Eastern guide, and the maps look similar, but there are important changes. The most important is the data used to generate the maps. As with most recent field guides, the data used for these maps has been provided by Paul Lehman, the foremost expert in North American bird distribution. The larger trim size of this book has allowed the thumbnail maps to be enlarged so that they are easily usable. This is a vast improvement over the Eastern guide, whose thumbnails were only useful for a vague impression of the species’ range.

On the other hand, a layout change here is a small step backwards. Each large map is assigned a map number, and the maps and species accounts are cross indexed – each map includes the page number for the species account, and each account indicates the map number. In the Eastern version, the accounts gave the associated map number immediately below the thumbnail map, where its significance is easily understood. In this combined guide, the map number has been moved alongside the species’ abundance. For example, one account shows “Fairly common M562”. In this position, the map number’s meaning is not immediately clear, and actually appears to be a qualifier for the abundance. But overall, this is just a small annoyance, and is in fact the only layout change that does not work.

Introduction and other sections

The introduction is largely unchanged from previous versions, and is broken down into the following sections:

- General ID techniques

- Songs and calls

- Bird nests

- Conservation

- Maps and ranges

- Habitats

- Subspecies and geographic variation

Compared to the introductory material of most recent field guides, it is very short and basic. Molt, for instance, is not mentioned at all.

This guide also includes:

- Quick index in the front

- Topography diagram of perched songbird and an outstretched wing

- Foreword by Lee Allen Peterson, one of Roger’s sons

- Editor’s note

- Life list (which takes up a surprising 13 pages)

- Silhouettes of roadside, shore, and in-flight birds

Video Podcasts

With the purchase of this book, you also get access to an extensive array of video podcasts. These short videos can either be watched online, or downloaded and played on your home computer or portable video device (such as video iPods). The categories of videos include family introductions, individual species accounts, birding techniques, and a biography of Roger Tory Peterson.

At the moment, before this guide is officially published, only a small sample of videos is available. More details and commentary on these podcasts is forthcoming.

Recommendation

This latest entry in the venerable line of Peterson field guides was designed to be an up-to-date resource for today’s birders, while at the same time a commemoration of Peterson’s work. Those goals have been met, but with some trade-offs.

As a resource, the updates have made it vastly superior to the Peterson regional guides. The increased size and weight, however, means that it is not practical to carry into the field. If you normally use one of the regional guides in the field, I would highly recommend adding this volume as a reference to keep in your car or home, much like how the large and regional Sibley guides work together.

As a tribute to Peterson, this volume is one of the best ways to appreciate his field guide art. True, much of the artwork has been altered, and some even replaced, but that sacrifice was necessary to ensure that this guide remains useful for identification. After all, that is its main purpose. Still, while examining this book I found a new appreciation for Peterson’s art. It is truly amazing, and looks fantastic here.

I can see myself referring to this new guide much more often than I did the Eastern. However, the treatment for some difficult groups (most especially the gulls) is lacking, and some important plumages and other images are missing (such as the female Eastern Bluebird, as mentioned in the comparison). Thus, as a reference I would rank this a bit below other recent field guides. But for me, the showcasing of Peterson’s art compensates for this, and makes it well worth having.

For more information on this guide, see its featured page.

Disclosure: I get a small commission for purchases made through links in this post.

Disclosure: The item reviewed here was a complementary review copy provided by the publisher. But the opinion expressed here is my own, it has not been influenced in any way.

(2 votes, average: 4.50 out of 5)

(2 votes, average: 4.50 out of 5)

[…] Peterson Field Guide to Birds of North America By Grant McCreary As with most recent field guides, the data used for these maps has been provided by Paul Lehman, the foremost expert in North American bird distribution. The larger trim size of this book has allowed the thumbnail maps to be enlarged so … The Birder’s Library – http://www.birderslibrary.com […]