Reviewed by Grant McCreary on May 16th, 2021.

You never forget your first field guide. As a kid, I had two: the classic Golden guide – by Robbins, Bruun, and Zim – and the National Audubon Society guide. You probably know the latter, with the fancy vinyl cover (or so I thought at the time). Oh, how I loved to look through that guide’s colorful photographs. I didn’t fully realize it then, but that guide has some serious usability issues. So I was excited to see a new Audubon guide set to be published this year.

The new National Audubon Society Birds of North America is, thankfully, not just a new edition of the previous Audubon guide; it is completely overhauled, essentially a completely new guide. Other than “National Audubon Society” on the cover and the use of photographs, there is not much similarity between this guide and the old ones.

To describe what this guide is like, this review will do something a little different. I will first attempt to provide the impression one gets from this guide, from picking it up for the first time to looking through some familiar birds.

The first thing one thinks when picking up the new Audubon guide: This thing is big! It is just about as tall as the ‘big’ Sibley guide, an inch wider, and a little thicker. It’s also heavy, weighing in at almost four pounds (63 ounces). That’s 15 ounces heavier than two of its main competitors, the Sibley and Stokes guides. Part of the reason is that it has a much higher page count – 910 pages, versus 625 for Sibley and 816 in Stokes.

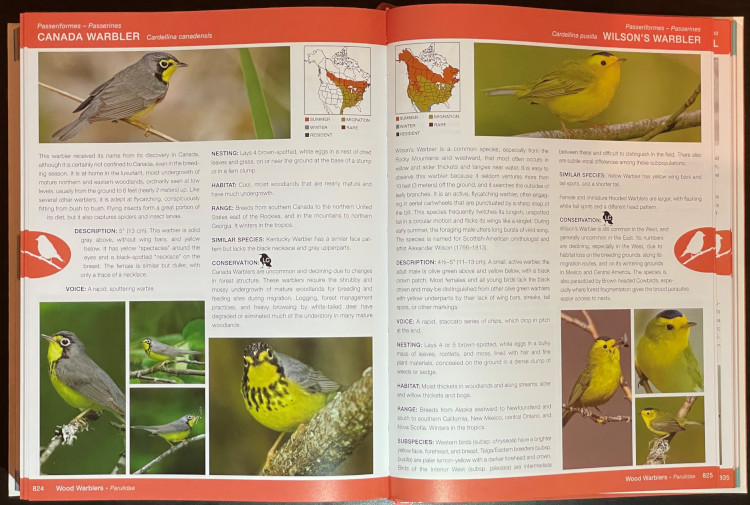

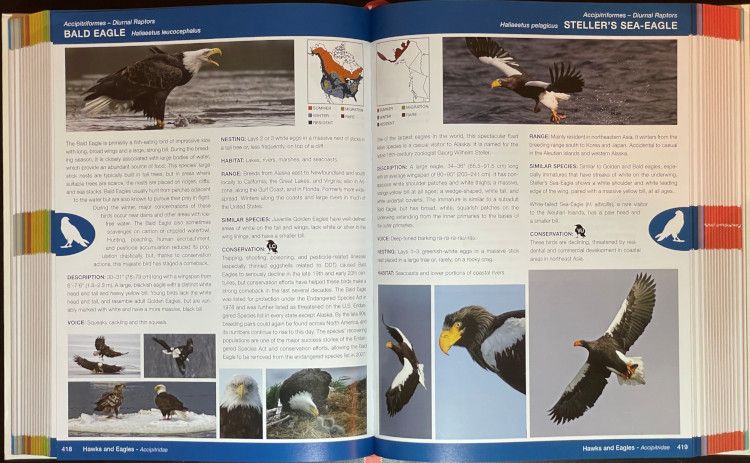

Upon opening the book, you will see that each page is fully dedicated to one species, with a range map and “banner” photograph at the top, text in the middle, and more photos at the bottom of the page. Flipping through a few pages shows that the species are organized taxonomically; for example, the falcons are between the woodpeckers and parrots, not with the hawks, as per our current understanding of familial relationships in birds.

When looking through any new field guide, I like to check out the warblers first. They’re one of my favorite groups of birds, and their diversity can be challenging for guides. Here are the observations I made while looking through these accounts:

- There are some really nice photos here. The selections for Tropical Parula particularly jumped out at me. There are some nice shots with “personality”, such as the Black-and-white Warbler perching with its head hanging underneath the branch.

- While some accounts have plenty of photos (such as the Tropical Parula), many of them are woefully incomplete. Here are some examples:

- Palm Warbler: No non-breeding birds. The text mentions “Adults in spring have a rufous cap”, but that does not fully convey the difference in how the birds appear most of the time (at least where I am in their winter range).

- Golden-cheeked Warbler: Based on this guide (photos and text), one would expect every bird to have a black throat.

- Wilson’s Warbler: All images show a black cap. Again, the text mentions that “most females and all young birds lack the black crown”, but the user should not have to rely on text for such a basic characteristic.

- Magnolia Warbler: No photo from underneath showing the half-black, half-white tail. The text description does mention the white in the tail, but it does so in such a way that, if I weren’t already familiar with the bird, I would not visualize it correctly.

- Golden-winged / Blue-winged Warblers: No pictures of hybrids.

- While checking the accounts to make sure that various plumages are included, it finally dawned on me that the photos are not captioned. Sex, age, breeding/non-breeding, much less sub-species or other information – the photos do not indicate any such thing. Can you imagine the confusion of a new birder expecting Yellow Warblers to have reddish heads, because half of the photos of that species show such a bird? Some such confusion could be cleared up by a careful reading of the text, but not all, and not easily by new birders.

- One account – Slate-throated Redstart – could instead confuse users by what it does show. Two of the four pictures show a bird with yellow, instead of red, underparts. Presumably, the yellow birds, which are found in the southern portion of this species’ latitudinally large range, are not found in the United States. Indeed, other prominent field guides do not include this form. A quick note in the description section of the account would clear this all up, but as it is users could easily be confused.

- Some of the pictures seem quite small. But upon doing a comparison with the Stokes guide, I found that while some are, indeed, small, on average they are about the same size as those in the other guide. However, the larger page size in Audubon means that these photos are relatively smaller on the page, thus contributing to the impression.

I’m going to come back to some of these issues, but first I want to detail the rest that this guide offers. The species text accounts consist of the following:

- Introduction – general information about the bird, including any particular behavior birders should look for

- Description – length in inches and centimeters; short description, including various plumages

- Voice

- Nesting – number and color of eggs; type and location of nest

- Habitat

- Range

- Similar Species

- Conservation – conservation status; population trends

The Audubon guide includes a well-rounded selection of information about birds. Most guides concentrate on just that which can be used to identify the bird, but this one also includes other information such as distinctive habits, nesting, and conservation. The latter, especially, is much appreciated; I wish more field guides would include conservation details. The trade off is that the descriptions are not as comprehensive and some field marks are unmentioned.

A range map is included for most accounts (excepting some vagrants), using distinct colors for summer, winter, resident, migration, and rare. I find it odd that some vagrants do not have any range map at all, while others do. Those that are included seem to be the only time that the ‘rare’ category is used; that color is not included on maps of otherwise common birds to indicate where they are, in fact, rare.

This field guide starts with an extensive, 24-page introduction that covers identification, birds at home, conservation, and various topics in biology. The latter includes such varied topics as avian cognition, confusing fall warblers, plunge-diving in seabirds, and molt. These are certainly interesting topics, though most of them do not have anything to do with identification, which is the primary purpose of a field guide. Presumably, however, these are included in order to get new birders interested in birds beyond identification, which I can certainly get behind. One thing normally found in field guides, however, is missing – bird topography diagrams. Such terms as flanks, breast, and mantle are used often in the species accounts. These are defined in a glossary in the back of the book, but it is much more helpful to show them on a diagram.

Other useful features of this guide include color-coded thumb tabs for groups of birds and a ribbon bookmark.

Ok, now back to some of the issues found during our first perusal. The effectiveness of a field guide lies largely in its illustrations. In order for the illustrations to work, they need to meet three criteria: they have to show the bird accurately and well; they have to fully represent the bird; and the user has to know what they are looking at. The Audubon Guide succeeds in only the first criteria.

There are simply not enough pictures in this guide to adequately show even basic species variability. In addition to the examples given previously, here are just a few others where a basic plumage aspect is conspicuously missing:

- Snow Goose – no blue morph

- Common Loon – no non-breeding

- Blue Bunting – no female

And extremely varied species such as many gulls and raptors? Forget about it.

The biggest offense is that there are no captions to any photo in the species accounts, no indication of sex, age, anything. How would the user know that this one is a male and that one a female, or that you would expect to see the bird look this way at a particular time of year? Or, even, that all the birds shown are the same species? In some pictures, they aren’t! The Ross’s Goose account has a great comparison shot of a Ross’s and Snow Goose, and there’s a nice picture of a Long-billed Curlew next to a Marbled Godwit in the former bird’s account. But without any indication of what’s being shown, those unfamiliar with the birds could easily get confused.

I found just one error: the Great Kiskadee account includes a photo of what appears to be a Myiarchus flycatcher.

Recommendation

The National Audubon Society Birds of North America is much improved from the earlier field guides to carry this organization’s name. It is pleasing to look at, with many large, striking photographs, and it includes a wide variety of information in the accounts, including conservation, which is much-appreciated. However, the deficiency in plumages shown and, especially, the complete lack of photographic captions severely handicaps this guide’s usefulness. Unfortunately, it cannot be recommended.

Disclosure: I get a small commission for purchases made through links in this post.

Buy from NHBS

(based in the U.K.)

Disclosure: The item reviewed here was a complementary review copy provided by the publisher. But the opinion expressed here is my own, it has not been influenced in any way.

My grandson and I are enjoying the Guide. However, we have found an important error. On page 138 the State of New Mexico is left out of the range of the Greater Road Runner. In fact, the Greater Roadrunner is the State Bird of New Mexico and is very prevalent in the City of Albuquerque!

Please correct this error as soon as possible

Sincerely and thanks for you work,

Judy Smith and Grandson Dylan Smith