Reviewed by Grant McCreary on August 18th, 2011.

At the beginning of 2011, The Crossley ID Guide: Eastern Birds was published with much fanfare. It seems like a new field guide is published every year, but a single look at this one will tell you that it is very different. I posted a peek inside the guide along with some preliminary thoughts in my initial review, but it’s (past) time to discuss this book in more detail.

Images

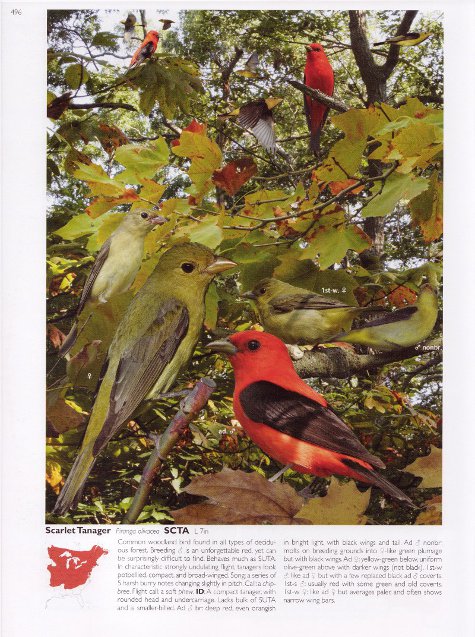

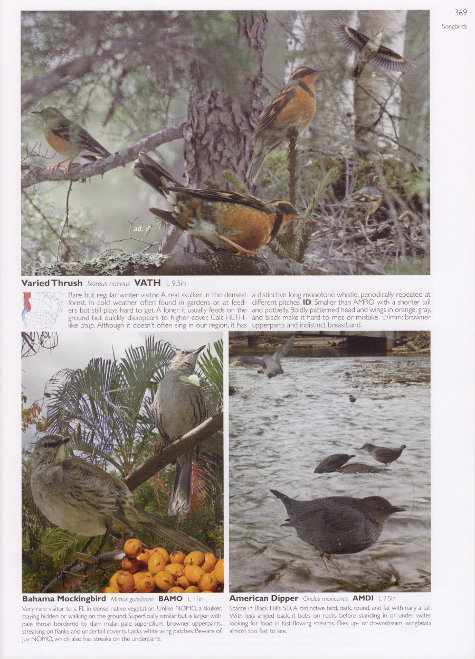

I have to start here. Crossley uses photographs to illustrate his guide. But instead of presenting them separately as other photographic guides have done, he incorporates all the pictures of each species into a single photoshopped montage.

The first thing you notice is the backgrounds. The birds are integrated into an appropriate habitat: ducks on water, warblers in trees, etc. Next, you realize how many birds are depicted in each scene. There are hundreds of some ducks, but most species, even songbirds, have at least a dozen. The birds are shown in various poses and at different apparent distances from the viewer. Thus, some birds will appear very large as if they were in a traditional field guide, while others may be so small or positioned in the background such that they are very difficult to spot. All of this is a part of what Crossley calls reality birding.

Crossley composed his plates to be “as lifelike as a printed image will allow” in order to show the birds as they actually appear in the field. This includes not only showing the habitat and positioning birds at varying distances, but also lighting conditions and partially obstructed views. It even includes behavior! If you see a bird doing something in one of these plates – for instance, a Rough-legged Hawk perched on a limb that looks much too small to support it, or a Blue-winged Warbler poking its head into a cluster of dead leaves – you can be sure that these actions are typical for the species.

Species Accounts and Maps

As striking as the pictures are, don’t neglect the text. Crossley starts with the bird’s status, habitat, and behavior. A terse description of vocalizations is given for some species. The ID section lists important field marks used to identify, age, and sex the bird (there’s a phrase in which context is everything). Only rarely mentioned are subspecies, hybrids, and the like.

Crossley’s accounts are very informal, making them memorable and unusually pleasurable to read. In fact, they often reminded me of Pete Dunne’s descriptions in his Essential Field Guide Companion. For example, see if you can tell what bird Crossley is describing with these statements (answers after the review):

- Tiny round ball of feathers with a cocked stub for a tail – nothing else like it!

- Sits at top of trees, with condescending stare.

The range maps use the standard three colors to indicate permanent, breeding, and winter ranges, with dotted lines to show approximate limits of irregular occurrence. Unfortunately, migratory range is not shown. The maps for full-page accounts look small on the page, but are really no smaller than the maps in other field guides. The maps of less-than-full-page accounts, however, are tiny and can be very hard to see. Oddly, some maps show the bird’s range across almost the entire continent, while others are zoomed in on the eastern half on which this guide focuses.

Other Features

Here are a few more aspects of the Crossley guide that you should be aware of:

- This Crossley ID Guide covers the eastern half of the U.S. and Canada (a western guide is in the works). Most regularly-occurring species in this region have full-page accounts. Rarities and vagrants generally get a quarter page and regional specialties a half page.

- This book differs from most field guides in that the species sequence is not strictly dictated by taxonomy. Instead, it groups similar families based on habitat and physical similarities. The order closely follows the sequence suggested in an article in Birding magazine, which shouldn’t be all that surprising since Crossley was one of its coauthors. In my opinion, the article presents a compelling argument. Now that I’ve seen it put into practice, I prefer it over a strict taxonomical ordering. It may take some getting used to (but see the next item in this list), but if all authors follow suit it will make field guides much more consistent and usable (though I’m not holding my breath on that).

- The inside-front cover and first page serve as a visual “quick find’ index, with unlabeled bird pictures representing the various families. A more detailed, 16-page key follows that shows just about every bird in the book (omitting most vagrants), this time labeled with alpha code (see next) and page number. The birds within each group are shown in scale, allowing for size comparison.

- In order to save space, Crossley makes heavy use of “alpha codes”, or bird-bander codes, as an abbreviation in the text. Many experienced birders have likely been exposed to these codes and will barely even notice their use. But I can see them being a bane to beginners. As Crossley notes in the introduction, the birds being referred to are often related, and thus close by. But I can still see some users having to refer to the alpha-code index in the back an annoying number of times.

- Don’t skip the introduction. If you haven’t already gathered it, this guide is a little different, so the “How to use this book” section is very helpful. There’s also a great, succinct discussion of how to be a better birder, along with an extensive set of labeled bird topography diagrams.

- Crossley’s website – Crossley Birds – includes 45 sample plates (as of right now) with expanded captions that give additional notes on identification and other interesting background information.

Issues and Errors

Inevitably, there are some issues with the Crossley guide:

- Even with all the photos, some plumages are still not illustrated. Immature Saw-whet and Boreal Owls are prominent examples (this seems to be a recurring theme with recent field guides) .

- As previously mentioned, most scenes are a full page with some being smaller. In order to reduce wasted space, the smaller ones are fitted together to fill a page. To accomplish this, sometimes unrelated birds had to be put together, which causes some aberrations with species order. For instance, you have to flip five pages from the regularly occurring mimids before you come across Bahama Mockingbird. This could have been avoided, but it would have made a big book even bigger.

- Some of Crossley’s plates are stunning to behold, more a work of art than utilitarian image. But a few, at least to me, just don’t look very good. The author has said that in order to keep the plates as realistic as possible, many of them are darker and less sharp than photos we’re used to seeing in field guides. That explains most, but not all of the poor images. There are some – I don’t know a better way to describe it – that look like an image scanned at low resolution. Even when viewing these pages from a normal distance, the colored dots that make up the image are distractingly visible. I have no idea whether this is due to the original images, all the processing done, or the printing process.

- In one interview, Crossley said that when it comes to identification, “size is just about everything”. It’s quite surprising, then, that the only measurement given in his guide is length (and then only in inches). Wingspan should have been included as well.

Crossley has listed a few corrections on his site. In addition to these, the White-eyed Parakeet account means to compare it to the very similar Green Parakeet, but the alpha code used is actually that of the African Gray Parrot (not very hard to tell apart!).

Purpose and Audience

The Crossley ID Guide, despite the category in which I classified this post, is not a field guide. Its size alone would preclude all but the most determined from carrying it with them while birding. Also, its design is not conducive to quick comparison between species. But this is by design. In the introduction, the author urges birders to not take a guide into the field. Further, although Crossley may be helpful in sorting out a difficult identification, it would not be the first reference I turn to when faced with such a quandary.

So if the Crossley guide isn’t for use during or after birding (not that you can’t, of course), what is its purpose? I think the value of this guide lies in learning birds before you go birding. Everything about this book is designed to familiarize the reader to birds as they actually appear in real life. This is a book to be studied – immersed in, really – at home.

The next question is who is it for? The quick and easy answer is anyone interested in North American birds! Intermediate birders may get the most from it, but I’d think that even experts would enjoy and learn something from this book. As for beginners, I tried to imagine how I would have reacted to the Crossley guide when I first started birding. The plates can be quite intimidating, and I’m not sure I would have had the framework to fully get everything shown and written in the book. But I still think that it would make a great learning tool, especially when used in tandem with a more traditional field guide. I can’t help but feel that if I could have studied with the Crossley and Sibley guides open to the same bird, I would have become a better birder faster. Actually, that wouldn’t be such a bad thing to do now.

One last thought: I wonder if Crossley’s unique photographic montages will better serve to engage beginners and even non-birders. Birds arrayed in static, consistent poses against a neutral background (a la Sibley) facilitates easy comparison, but no matter how accurate or attractive the illustrations are, they aren’t alluring to anyone who’s not scrutinizing them for the sake of identification. Other photographic guides showcase gorgeous portraits of birds (like the recent Stokes field guide or, especially, the Sterry and Small guides), but they still aren’t relatable to the uninitiated. But Crossley’s images grab the viewer and forces contemplation, or at least awareness, of birds as a part of our world.

Recommendation

The amount of work that went into The Crossley ID Guide: Eastern Birds is staggering. It contains 640 scenes, composed from more than 10,000 photographs (nearly all taken by Crossley himself!), that present the birds of eastern North America in a unique and lifelike manner. I don’t know if it will revolutionize field guides; probably not, though, if for no other reason than I don’t know if anyone other than Crossley could produce a guide like this (I’m only half joking). Still, the Crossley guide has become my go-to source for learning birds, and it is simply a pleasure to browse through. I highly recommend it.

Answers:

- Winter Wren

- Northern Hawk Owl

Disclosure: I get a small commission for purchases made through links in this post.

Disclosure: The item reviewed here was a complementary review copy provided by the publisher. But the opinion expressed here is my own, it has not been influenced in any way.

Comment