Reviewed by Grant McCreary on November 4th, 2011.

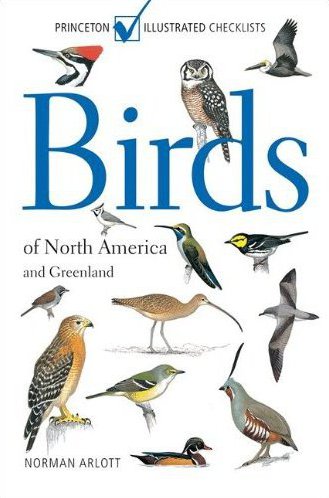

Birds of North America and Greenland is the latest entry in the Princeton Illustrated Checklists series. (It was also published in the UK as Collins Field Guides: Birds of North America.) You may be wondering what they mean by illustrated checklist. Though this book is little, it is more than a mere list of birds found in this region accompanied by illustrations. But it is also not a full-fledged field guide. Think of it as a “lite” field guide.

This guide includes nearly every species recorded in the lower 48 states, Alaska, Canada, and Greenland – over 900 birds. Some recent additions to the region – whether vagrants or “splits” (discussed below) – are missing. The standard field guide format is followed, with the illustration plates on the right and species accounts on the facing page.

Illustrations

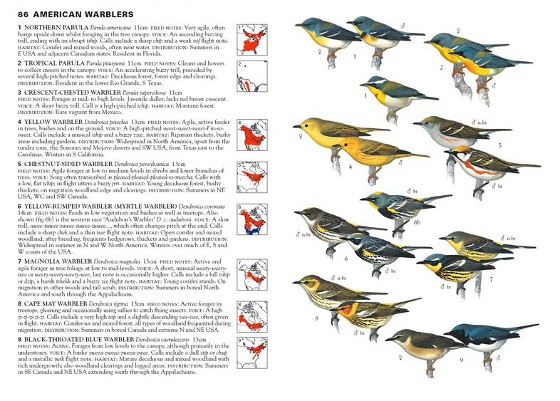

Birds of North America and Greenland is illustrated with the author’s own paintings. As I mentioned in my review of Birds of the West Indies, also by Norman Arlott, I find his work to be very attractive. The illustrations are labeled as male/female and breeding/non-breeding where appropriate. Annoyingly, instead of the species’ names, numbers are used to identify the birds on the plates.

The concise format means that not all plumages were included. Most male/female and breeding/non-breeding plumages are displayed, with warblers being the most glaring exception (all having at most two birds illustrated, with the exception of Yellow-rumped and Palm Warblers). Some geographic variation is illustrated, but not any immature or juvenile birds, which could cause some identification headaches. The only birds shown in flight are seabirds (only in flight), pelicans, raptors, jaegers, swifts (only in flight), and swallows. Oddly, the gulls and terns are only shown perched, even though the former were also shown in flight in the West Indies guide.

Species Accounts

The text accounts include:

- Size – length in centimeters

- Field Notes – brief notes on behavior, identification, and subspecies

- Voice

- Habitat

- Distribution

The “Field Notes” impart some useful information, but not nearly enough to differentiate between similar species, leaving you to decipher that yourself from the plates (which don’t show all possible plumages!). For example, the author mentions that some Philadelphia Vireos are drabber than the one shown and look much like Warbling Vireos. But nothing is mentioned of how you can differentiate such birds.

Range Maps

Breeding, winter, and permanent ranges are shown on maps with country, but no state or provincial, boundaries. These maps are extremely small and tucked into the inside margin – to the right of the text – where they are hard to see. Perhaps a better placement would have been on the outside of the page, to the left of the text. They give a rough idea of where the bird occurs, but nothing more.

Issues

Even a cursory reading of this guide revealed errors like incorrect alternate names, labels, and sizes. Rick Wright noted the same in his review, including the use of the wrong illustrations for European Starling. No field guide is going to be error free, but the amount of them here is more egregious than most.

Taxonomy is always in flux, but this guide seems especially out of date. The latest AOU updates are not incorporated, but that is not a surprise or issue. However, neither Winter Wren nor Whip-poor-will has been split (based on the 2010 AOU update); although in each case the text mentions the possibility of one.

Lastly, it is worth mentioning that since Birds of North America and Greenland was originally published for a European audience, Arlott has chosen to use some names that may be unfamiliar to North American users (with other names given in parentheses). Here are a few examples:

- Great Northern Diver (Great Northern or Common Loon) – “Diver” being the European preference

- Snipe (Common or Wilson’s Snipe) – Considers Common and Wilson’s as races of the same species

- Chuck-wills-widow (Carolina Chuck-will) – I’ve never heard that alternate name before

- Blackbird (Eurasian Blackbird) – Many birds also (or primarily) found in Europe are listed as just a single name

- Grey Catbird – uses the English word forms, such as “grey”, even for birds that are indigenous to the Americas

I’m disappointed that Princeton didn’t change these to make this book more user-friendly to their North American audience.

Recommendation

The appeal of Birds of North America and Greenland is that it illustrates all of the birds of North America (minus Mexico, of course, and the latest splits) with very nice paintings for a low price. I was able to reliably use the Illustrated Checklist for the West Indies in the field, but would not be able to do the same with this one. The number of possible birds is too great, and the lack of variation depicted and identification information in the text will too greatly handicap efforts at identification. Because of this and the various issues (especially the fact that it is not user-friendly to birders within this region), I cannot recommend this guide to anyone here in North America. It could, however, be of use to visiting ecotourists and general wildlife enthusiasts, or those who may never visit but want to know what our birds look like.

If you want to take a closer look at some plates and text, there are more examples at Princeton University Press.

Disclosure: I get a small commission for purchases made through links in this post.

Disclosure: The item reviewed here was a complementary review copy provided by the publisher. But the opinion expressed here is my own, it has not been influenced in any way.

Comment