Reviewed by Grant McCreary on June 30th, 2019.

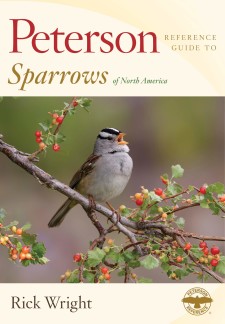

Bird family guides, or monographs, have been a prominent part of birding literature since there have been bird books. But do we need any more? Now, I’m not questioning if sparrows in particular are worthy of such treatment – they are. Rather, is there a need for any further family reference guides? As a lover of such books, it pains me to even ask. But when the bulk of their usual contents – natural history information such as how many eggs a bird lays, its preferred habitat, or just about any other such tidbit one may need – can easily be discovered by anyone with an internet connection, why would they need a printed book? Rick Wright provides an answer to that question with Peterson Reference Guide to Sparrows of North America.

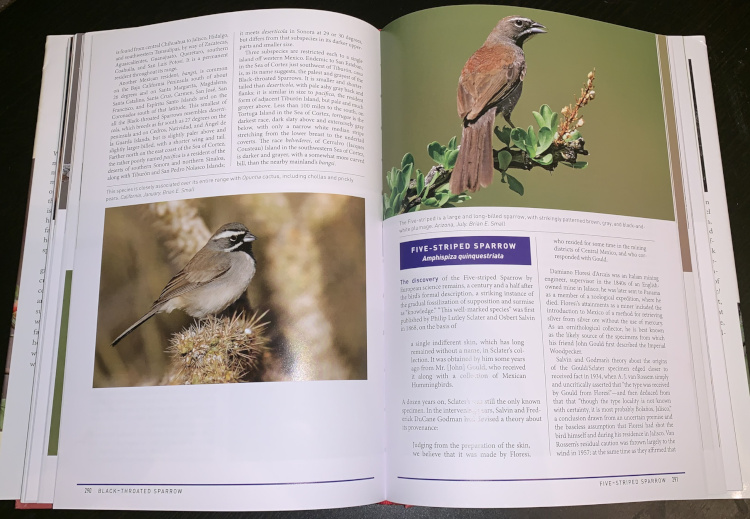

From the very first sentence you can tell that this will be a different kind of bird book. Wright commences: “Most bird books treat their subject as one entirely separate from the cultural world that humans inhabit, focusing exclusively on what for the past 2,500 years we have called ‘natural history’.” He goes on to say that “birds have a human history, too…made up not just of facts and measurements but of stories.”

To see just how different this guide is, it’s useful to compare it to previous entries in this series. Sparrows is the third book in the Peterson Reference Guide series to treat a single family, following Owls and Woodpeckers. The species accounts in those books cover the following topics:

- Measurements – length, wingspan, mass

- General notes

- Systematics, Taxonomy, and (in Owlsonly) Etymology

- Distribution

- Description and Identification

- Vocalizations

- Habitat

- Behavior – including Breeding

- Status/Conservation

Contrast that with the contents of the accounts in Sparrows:

- General notes

- Field Identification – including vocalizations

- Range and Geographic Variation

As you can see, most of the “natural history” information is not to be found here. As to what is here, the accounts start with “one or two anecdotes that illuminate the confrontation between humans and birds over the years.” These anecdotes typically focus on taxonomy, for “much of a bird’s human history is revealed in its changing taxonomy.” Many readers may be turned off by the notion of reading taxonomic history – how a species’ names change over time. Understandably, as this could be some really dry stuff. But Wright teases out moments of discovery and…well, intrigue may be too strong a word, but certainly interest. The accounts are filled with the names of early ornithologist with which birders will certainly be familiar, often as namesakes of these very same sparrows. Their discoveries are exciting, and the knotted puzzles they had to work out lead to knowledge that we birders take for granted today.

Just one example of the discoveries referenced here is that at least a few of the Hessians – the mercenaries employed by the British during the American Revolution – made significant contributions to American natural history. One of them sent to a European zoologist what would become the type specimen of the Red Fox Sparrow.

The remaining textual sections are much more extensive than you will find in most identification guides. All that detail, though, is a bit much to get through unless you really need it. So for basic identification or range questions, I would first consult a regular field guide or Sparrows of the United States and Canada: The Photographic Guide (which is now out of print, so may not be an option). But for really thorny or cutting-edge identification issues, like Brewer’s vs. Timberline or the Sagebrush-Bell’s complex, I would consider this reference guide an essential text.

While perusing this section you can also run into some really interesting information not strictly related to identification. For instance, the well-known White-throated Sparrow occurs in two morphs – white- and tan-striped. Wright, of course, gives us the history of ornithological thought on the subject. But our current understanding – that the morph occurs in both males and females and is tied to behavior differences that affect breeding choices – is the most amazing one of all.

Likewise, the Range and Geographic Variation section contains a lot of words that can be summed up in a range map in most cases. Unfortunately, you will not find any such maps here, so I highly recommend having another resource – whether field guide or eBird – handy while using this guide. Again, however, for more than a basic understanding of range this section is quite valuable, as it includes details that you cannot ascertain from a high-level map. This section also includes the particulars of subspecies and other recognizable variants, whose range information that is even harder to find on maps.

Peterson Reference Guide to Sparrows is filled with photos, but not as prominently as the previous entries in this series. Most species are illustrated adequately, often by an always-impressive image from Brian Small. A few, however, have just one or two photos. I was most disappointed with Black-chested Sparrow. I was unfamiliar with this eye-catching bird until I saw a picture of it in the introduction. Looking for more, I found the species account had but a single, poorly-lit photo. It’s odd that the best photo was used in the introduction. On the whole, the pictures adequately illustrate this guide, but again, this wouldn’t be the first place I would turn for identification help (though, to be fair, it doesn’t purport to be an identification guide).

Finally, some of the names of birds here may look a little different from what you’re used to, or entirely unfamiliar altogether. Wright dispenses with the apostrophe in the possessive bird names. So here, it is Baird Sparrow and Botteri Sparrow. The rationale given is that the possessive name “misunderstands the true signification of the Latin genitive in such situations” and that it makes it ambiguous whether one is referring to a species name or actual ownership, say of a given specimen. I don’t follow the first argument, not knowing anything about Latin, and think the second one tenuous (capitalization of bird names would take care of that). But I’m ambivalent about this change; it takes some getting used to, but isn’t a big deal.

You may, however, see some bird names in the guide that you don’t recognize at all. The author warns in the introduction that “not all of the taxa considered here are accorded species status” by the American Ornithological Society, whose Check-list is followed by most major field guides. But many of these the reader will, no doubt, already be familiar with in some capacity as they are treated by many field guides, such as the various forms of Dark-eyed Junco and Fox Sparrow. The Savannah Sparrow complex, treated here as five species – Large-billed, Belding, San Benito, Savannah, and Ipswich – may not be quite as familiar (or maybe that’s just the perspective of a birder who lives in an area in which just the “regular” Savannah is expected).

In a work such as this, it’s not surprising to find errors that slip through. The caption for the photo of a Bridled Sparrow on page 343 is misplaced, it actually refers to a photo of a Black-chested Sparrow on the next page. And I question if the right Song Sparrow subspecies is given for the picture on page 44 (it may be correct, but doesn’t seem to jive with the text).

Recommendation

So…are family guides still relevant today? Peterson Reference Guide to Sparrows of North America shows that they can be. But is it worth having? If you’re looking for basic identification or natural history information, then no, a specialized identification guide or online resources would serve for that. But if your interest in the sparrows goes beyond that to, among other things, range and identification of subspecies and their human history, then it is well worth having. I think the human history aspects alone make it worthwhile. How many reference guides can you pick up, turn to any species, and get a good story?

Disclosure: I get a small commission for purchases made through links in this post.

Buy from NHBS

(based in the U.K.)

Disclosure: The item reviewed here was a complementary review copy provided by the publisher. But the opinion expressed here is my own, it has not been influenced in any way.

(1 votes, average: 4.00 out of 5)

(1 votes, average: 4.00 out of 5)

Comment