Reviewed by Grant McCreary on October 26th, 2010.

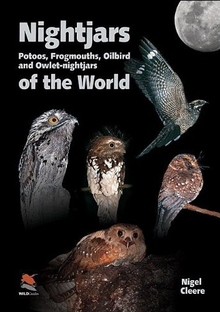

Often, it seems like the flashy, rare, or hard-to-identify birds get all the attention. There are plenty of books on wood-warblers, the Ivory-billed Woodpecker, and gulls. (Not that there’s anything wrong with that.) Although some are certainly endangered, and silent birds can be hard to identify by sight, nightjars don’t usually fit into those categories. So I was pleasantly surprised to see Nightjars of the World, a new photographic guide to these enigmatic birds.

The birds included in this book (which I will collectively refer to as nightjars, even though technically that is just one of the families treated) are nocturnal and secretive. They are usually known for their repetitive, yet evocative, calls. But beyond these calls that “jar” the night, they are incredibly fascinating. Did you know that the Oilbird is the only known nocturnal fruit-eating bird? Even more amazingly, it is one of a very few birds that uses echolocation to navigate (like bats). Although several nightjars are known to enter brief periods of torpor (when an animal reduces body temperature and metabolic rate to conserve energy), the Common Poorwill is the only bird that may truly hibernate.

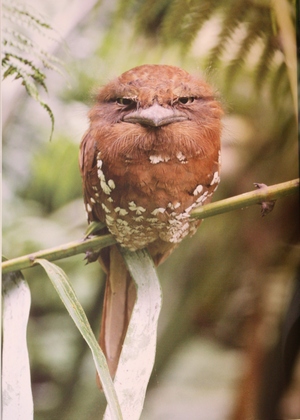

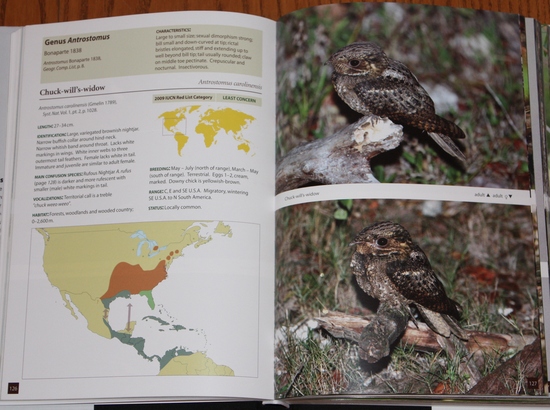

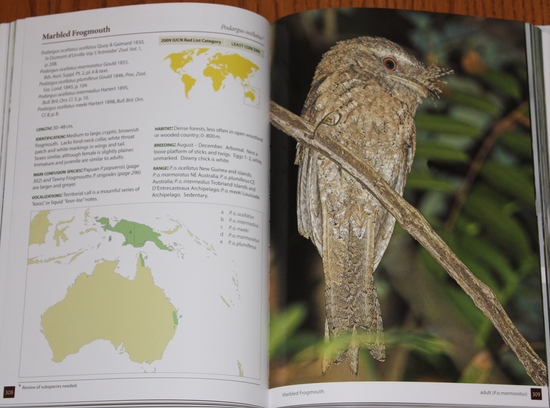

Flipping through this book, you will see many similar-looking birds that are a study in cryptic patterns of brown, gray, and rufous. That may sound boring, but nightjars have a subtle beauty that really shines through these wonderful photographs. But there are also some undeniably spectacular species, as well as crazy-looking ones like the Sri Lankan Frogmouth that, according to my wife, “looks like a Muppet”.

Doesn't this bird look like a Muppet?

Each account starts with text and range maps on the first page (and rarely a photo), followed by one or more pages of photographs, which are the undisputed highlight of the book. Each species is portrayed by 2-8 photos (on average three and a half). They are fantastic, and very large. The pictures of most nightjars occupy half a page, while those of the more upright potoos, frogmouths, and owlet-nightjars take up an entire page.

About a dozen of these 135 species are illustrated primarily, or even entirely, by photos of museum specimens. But many of these are known with certainly only from such specimens. Amazingly, one of these, the Nechisar Nightjar, is known from just a single wing found on an Ethiopian road (google the species or see the fascinating Atlas of Rare Birds for more details). This, combined with these birds’ secretive habits, makes it amazing that such a large number of photos have been included, much less photos of such high quality.

However, I do wish that more species were shown in flight. Granted, most encounters with nightjars will be of perched birds, and getting good in-flight shots of them must be incredibly difficult. But there have to be some available for the more common species (don’t there?). Personally, being in the eastern United States, I would have loved to see an in-flight comparison between the Whip-poor-will and Chuck-will’s-widow. Plus, there are some members with elongated tail and wing feathers that would be spectacular to see in the air. However, such pictures are included for seven of the ten nighthawks, which are most commonly seen in flight, and a very select few other species.

The textual accounts include the following:

- English Name – some are different from the “official” names, in which case there is a note explaining the difference

- Scientific Name – includes full citation giving name, author, year, and place of publication (for each subspecies!)

- Length – in centimeters

- Identification – description of species, with differences based on gender and age where appropriate (and known)

- Main Confusion Species

- Vocalizations

- Habitat – including altitudinal range

- Breeding – summary of when and where; clutch size; description of eggs and chicks

- Range

- Status – uncommon, abundant, etc

- 2009 IUCN Red List Category – “Least Concern”, “Endangered”, etc

That is a fairly extensive list, but the accounts are actually disappointingly sparse. The list of similar species seems incomplete. Whip-poor-wills and Chuck-will’s-widows, for instance, aren’t listed for each other. (It can’t just be me that can have difficulty with them given poor views.) A flight call is described for relatively few species; otherwise just the main territorial call is given. Further, it would have been nice to include some information on feeding and other habits.

To be fair, some of this information is simply not available. Nine of these species have never had their vocalizations described at all, much less other details of their lives (there are a lot of question marks in this book). But a cursory examination of these species’ accounts in volume five of the Handbook of the Birds of the World reveals additional particulars, like flight calls and feeding habits, that could have been included here for many species. Their absence in this newer book is all the more surprising given that Cleere also authored the nightjar family account in the Handbook.

The range maps are relatively large and use distinct colors for permanent, breeding, and non-breeding ranges, with arrows indicating migration routes. Major rivers and country boundaries are displayed, but inter-country political boundaries are not. For large countries like the US, this can make the maps more difficult to decipher than they should be. However, subspecies ranges are labeled for polytypic species, which is very welcome.

There are actually two maps for most species – the detailed map described above and a smaller map of the entire world with a box outlining the area shown in the detailed map. The world map will be of help to the severely geographically challenged, but the actual maps aren’t zoomed in far enough to confuse most readers. Even for very range-restricted species in South America, the “detailed” map shows the entire continent. For the most part, I feel that they are a waste of space that could have been devoted to more text or photos.

A 50 page introduction covers distribution, plumage and structure, general biology (including communication, food, breeding, and camouflage), and taxonomy. A good bit of the page count comes from tables, figures, and a generous amount of photos, but it provides a good background on these birds.

Finally, I’d like to mention that this is a beautifully produced and designed book. The binding, paper, and printing are of very high quality. The layout is simple, but very attractive. There’s one thing that could have been done to improve it, though. Among the appendices in the back is a list of photographic credits that gives location, date, and photographer for each of the book’s 587(!) photos. I’m glad this was included, but the location and date would have been much more useful if placed adjacent to the photos themselves.

Recommendation

I wish the text was more extensive and that additional in-flight photos were included, but Nightjars of the World will still help birders to identify these birds. But even so, I don’t think that’s the primary value of this book. One of my favorite and most sublime birding moments was studying a Common Pauraque in the daylight as it was roosting right next to a trail. This guide can’t quite replicate such an experience, but it does reveal the subtle beauty of nightjars that absolutely floored me that day in Texas. If you aren’t already a fan of nightjars, this book will convert you.

Disclosure: I get a small commission for purchases made through links in this post.

Disclosure: The item reviewed here was a complementary review copy provided by the publisher. But the opinion expressed here is my own, it has not been influenced in any way.

A review by the author?

What a shame!

Huh? The review is mine.

Sorry Grant but the line “Reviewed on October 26th, 2010 by Grant McCreary” it is so small in that i didn’t see it.

By the way: great review!

Cheers

Ah. I see what you mean, though. After trying to take a fresh look at the page, I can see how it could be confusing. I’ll have to see what I can do about that.

And thanks!