Reviewed by Grant McCreary on December 19th, 2014.

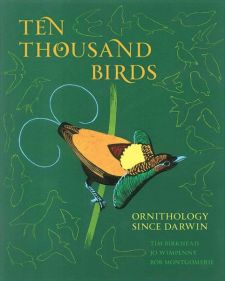

Ten Thousand Birds: Ornithology since Darwin. Sounds like a real page-turner, huh? I know that a book on the history of ornithology might not sound very interesting, especially a volume as thick as this one (if it does, then feel free to skip this review and go ahead and get this book, you won’t regret it). So, even before getting into the book itself, let me explain why you should read this book.

If you study birds for a living, or are planning to become an ornithologist, it should be pretty clear that you need to know not only what is currently known about birds but also how we came to that knowledge. I don’t know if that is taught in ornithology programs, but if not, then this book is an excellent survey of what is known. But that “knowledge” also might be wrong. Using for an example Julian Huxley’s rejection of female choice in sexual selection (now widely acknowledged), the authors demonstrate that “it is all too easy for an entire generation of ornithologists, including some senior figures, to become trapped within a particular paradigm.” Is it possible, they then ask, that the same thing is happening today with the widespread acceptance of female choice?

Ten Thousand Birds is not just for professionals, it should also be read by birders and anyone interested in birds beyond their identification. It presents a broad selection of topics, from migration to breeding to conservation. It’s almost like a mini-course in ornithology. The authors include this quote from Richard Feynman, which sums up nicely why this is important:

You can know the name of a bird in all the languages of the world, but when you’re finished, you’ll know absolutely nothing whatever about the bird….So let’s look at the bird and see what it’s doing-that’s what counts. I learned very early the difference between knowing the name of something and knowing something.

Ten Thousand Birds may seem intimidating, with its large size and treatment of some very technical topics. But the authors have done a commendable job in making it accessible and actually interesting. They do that by not trying to include every relevant person and idea in the last 150-some years of ornithology. Instead, they have “identified what we considered the most exciting and interesting findings in ornithology and how those subjects and the people that worked on them helped to transform biology”. To that end, they have organized the book by topic, essentially “a set of essays on key ornithological topics whose development we explore from Darwin to today.” These include:

- Yesterday’s Birds (the origin of birds)

- The Origin and Diversification of Species

- Birds on the Tree of Life (taxonomy)

- Ebb and Flow (migration)

- Ecological Adaptations for Breeding

- Form and Function

- The Study of Instinct

- Behaviour as Adaptation

- Selection in Relation to Sex

- Population Studies of Birds

- Tomorrow’s Birds

Another way they’ve made the book more readable is by focusing on people and even relationships between ornithologists. And some of these people and relationships were, shall we say, interesting. One extreme example was the “Systematics Wars”, about which the authors write:

While not everyone likes this term, to those of us looking in from the outside, systematists at the time seemed clearly at war, as egos and emotions ran high, and the field seemed to attract some of the most arrogant, opinionated, and downright nasty individuals who have ever called themselves scientists. It would take some serious psychological research to uncover the reasons for this.

You’ll learn plenty here. One of the crazier things was that a psychologist in the 1940’s had trained pigeons to guide missiles to their targets. “Project Pigeon” was eventually abandoned, but he achieved a higher degree of accuracy than anything else that had been tried. (I’m sure the pigeons were relieved, as it involved them riding in the missile’s cone.) More seriously, there’s a potential answer as to why brood parasite hosts don’t reject foreign chicks, even when they are so much different than their own. Presumably, the birds would imprint on the chicks in their initial brood. If, in subsequent broods, there is a chick that is different, they would reject it. But what if their very first brood was parasitized? Then they would imprint on the wrong type of chick, and would reject their own offspring in future nesting attempts. So overall, it’s better for them not to imprint like that (and even if some did, they wouldn’t be able to pass on the trait since they would never raise offspring of their own).

In a book that has dealt so much with the biology and evolution of birds, the final chapter – Tomorrow’s Birds – sounds like it could be about the next evolutionary steps for birds. Rather, it’s about something much more immediate: conservation. This seems a bit out of place, but as the authors note: “conservation…requires clear, logical – scientific – thinking to best identify how problems are addressed” and “it is only through our knowledge of bird biology and bird numbers…that we have any chance of saving what we have left.” This puts all the previous content – indeed, everything that I’ve read about birds – in an entirely different light. As the authors have shown here, studying birds is fascinating stuff and you can read Ten Thousand Birds, or one of the myriad other books on bird biology and behavior, strictly for the knowledge and enjoyment of it. But there is a practical application of that knowledge that makes it all the more precious – saving birds.

This book includes a good many illustrations, mostly photographs of the people discussed. Each chapter also has a helpful timeline of important events and publications related to the subject.

The only thing that’s missing from Ten Thousand Birds is a glossary. While the authors do a decent job of explaining terms and principles of the subject at hand, other terms, such as “sympatric”, are used without any definition.

Recommendation

Ten Thousand Birds: Ornithology since Darwin is an excellent summary of what we know about birds and how that knowledge was gained. As such, it is indispensable for students and practitioners of ornithology, or anyone else interested in the study of birds. It’s a good read, and since it’s organized by subject you don’t have to read it straight through, but can skip around according to your interests.

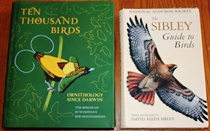

I’d also highly recommend Tim Birkhead’s The Wisdom of Birds: An Illustrated History of Ornithology. It covers many of these topics prior to Darwin. If anything, it’s even more interesting and enjoyable than this volume!

Disclosure: I get a small commission for purchases made through links in this post.

Buy from NHBS

(based in the U.K.)

Disclosure: The item reviewed here was a complementary review copy provided by the publisher. But the opinion expressed here is my own, it has not been influenced in any way.

Comment