Reviewed by Grant McCreary on June 11th, 2010.

Birds are beautiful. Ok, so vultures aren’t the most visually appealing creatures around. But birds, from the most fantastical bird-of-paradise to the plainest sparrow, have an undeniable beauty. Color is the primary component of their attractiveness and one of the most noticeable characteristics of these remarkable creatures. But how much do we, as birdwatchers, actually know about these colors? How do birds produce them? What purpose do they actually serve?

In Bird Coloration, Professor Geoffrey Hill answers these questions and many more. He starts by introducing basic terminology and describing color variation and how birds see colors. He then moves on to the production of colors and how a bird’s genetics and environment influences them. Finally, there is a discussion of the functions and evolution of coloration.

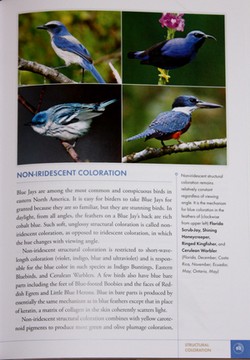

The information presented here is, in a word, fascinating. I thought I knew a good bit about bird coloration, but I found myself learning something new on every page. You may already know, for instance, that blue feathers are not the result of pigment but rather arise from the structure of the feathers themselves. But the author demonstrates exactly how this works. Even better, he shows us what happens when the structural components are missing or don’t work as they’re supposed to (in the form of an all white Steller’s Jay). Here are just a few additional interesting facts:

- Many otherwise entirely white birds have black flight feathers. This is because the melanin that makes the feathers black also makes them more durable. Hill illustrates just how important this is with a startling case of an albino Great Frigatebird. This bird’s flight feathers were completely abraded away (by air), leaving it flightless and doomed. The picture is unbelievable.

- Color can be used to scare up prey, as when Northern Mockingbirds and American Redstarts flash their colorful wings and tails. But it has also been shown to be the case in penguins; their contrasting plumage startles fish into leaving protective schools, thus making them easier to catch.

- Contrary to what you would think, dark plumage keeps birds cool in hot climates, while white birds are warmer in cold weather.

- Black masks are very common in birds, and can serve many different functions. They hide eyes, making the bird less conspicuous, they reduce glare, and can be a signal in dominance interactions and help to attract mates.

- The dark upper mandible of Willow Flycatchers reduces glare, allowing them to forage in non-shaded habitat.

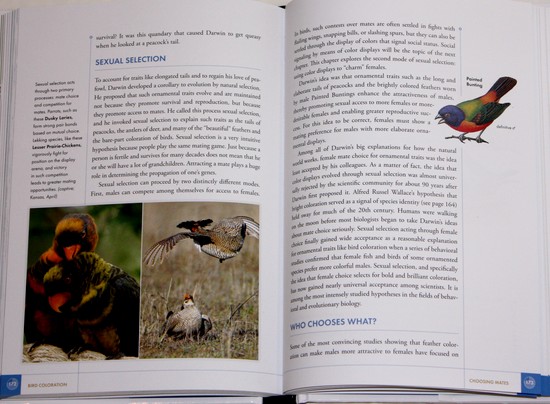

One of the best things about this book is that, for all of the interesting information it contains, it encourages you to ask your own questions and think for yourself. For instance, male American Redstarts have a delayed definitive plumage, where they look similar to females during their first year even though they are capable of breeding. Hill presents some possible advantages of this scheme. But what isn’t mentioned is why don’t other sexually dichromatic warblers do this? I wonder what it is about the redstart in particular that it possesses this trait but others don’t. In the same way, likely reasons for a distinct juvenile (or juvenal) plumage are given. But there are some birds, such as Downy and Hairy Woodpeckers, where the immature females look similar to adult females, but the young males have their own plumage (a red crown in this case). Why would the young males need to look distinctive but females do not?

Hill wrote this volume for non-professionals, especially birders. He did a commendable job in making a very complicated, technical topic not only readable, but also enjoyable. There were a few instances where I thought he simplified things too much, but for the most part, I felt that the writing level was spot on for the target audience. Also in keeping with this, sources are not cited in the text, but are rather listed by chapter in the back.

The topics presented here are incredibly interesting, but are they important for non-professional ornithologists to learn? It is the author’s opinion that “few realms of study improve the competence of a birder more than learning about avian coloration”. I’m not entirely convinced of that, but it is certainly relevant for all birders.

Here’s a practical example of how the knowledge of color formation can be useful for birders. Recently, an unusual light-blue bird was photographed in southern Georgia. Superficially, it looks very much like a Blue-gray Tanager, which would be a major find. However, David Sibley has identified it as a Painted Bunting, even though it doesn’t look like any Painted Bunting depicted in any field guide. If you ignore the color, you’ll see that it looks good for a bunting, but it could plausibly be a Painted or Indigo Bunting based on location. Green feathers, like those on a female-type Painted Bunting, are the product of yellow pigment combined with blue structural coloration (remember yellow plus blue makes green?). Thus, you could reasonably deduce that this bird is a female-type Painted Bunting that lacks yellow pigmentation, leaving just the blue color from the feather structures.

Naturally, you can’t discuss bird coloration and not actually show birds and their colors. You will find plenty of colorful birds here, mostly in the form of photographs along with some paintings taken from the National Geographic field guide. The illustrations, especially the photos, are certainly attractive, but they mainly serve to reinforce the concepts mentioned in the text.

Recommendation

Color permeates every part of a bird’s life. Knowing how birds perceive, produce, and respond to color will grant insight into their lives and behavior, and even hone your skills as a birder. If that sounds good to you, then I highly recommend National Geographic Bird Coloration.

Disclosure: I get a small commission for purchases made through links in this post.

Comment