Reviewed by Frank Lambert on January 31st, 2021.

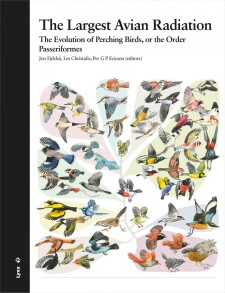

During the last two decades, technological advances in DNA studies, particularly the speed, reliability, and accuracy of them, has resulted in an incredible output of high-quality research. The results have regularly bewildered and surprised avian taxonomists, ornithologists, and birders, and upended a lot of presumptive taxonomic thinking. Not only have we witnessed a dramatic increase in the number of recognised bird species, but our interpretation of the evolutionary relationships between these species and their classification has fundamentally altered our understanding of phylogeny (the hypothetical evolutionary relationship amongst taxa), the substance of this hefty book. The Largest Avian Radiation: The Evolution of Perching Birds, or the Order Passeriformes is essentially an interpretation and integration of the results of hundreds of recent studies, providing the reader with a detailed summary of our current understanding of the taxonomy and historical relationships of passerine birds. The 22 authors are based in a number of respected academic institutions, primarily in Denmark, Sweden, France, Brazil, China, and USA.

These DNA-based studies have frequently shown that earlier taxonomic treatments, particularly at the family level and above, are not what we had thought and that a considerable number of species have been misclassified in the past. This book is an attempt to set the record straight, and to propose a new classification and linear taxonomy based on the evolutionary history of passerines. Who would have thought, for example, that Rufous-throated White-eye, endemic to Buru in the Moluccas of Indonesia, would be shown to be an aberrant arboreal montane forest pipit, now called Madanga Anthus ruficollis? Or that Pale Rockfinch Carpospiza brachydactyla is also a member of the pipit family Motacillidae rather than a sparrow? Another example of where DNA studies have uncovered unexpected results is that of the Sapayoa (Sapayoa aenigma), a drab inhabitant of the Chocó rainforests of South America, which looks remarkably like a manakin, but is in fact the only known representative of the “Old World” suboscines (broadbills, pittas and asities) in the Neotropics, and furthermore, best placed in its own family, Sapayoidea. Incredibly, some species are still classified as incertae sedis, meaning that their relationship with other birds is still unresolved. For example, consider the case of Crested Jay Platylophus galericulatis, which lives in the lower levels of rainforests in parts of Southeast Asia. Although it has a very odd call, it looks remarkably like a crow and has long been considered as one, but recent genetic studies suggest it is most likely closely related to the crowned shrikes (Eurocephalus) of Africa.

With more than 6,200 species, the perching, or passerine, birds represent one of the most remarkable proliferations of species, comprising 60% of avian diversity. Present evidence shows that the passerines originated during the early radiation of modern birds, which occurred on the austral continents (South America, Antarctica, and Australia) after a world-wide catastrophe had wiped out most ancient terrestrial life, including large dinosaurs and early birds. Subsequently, members of the Order Passerines rapidly diversified and spread across all continents except for Antarctica.

The traditional classification of birds, which was mainly based on comparative anatomical studies made more than 100 years ago, could do little to resolve the relationships among passerines because they were generally too anatomically uniform. Therefore, the classification that was used for most of the 20th century was for the most part a practical arrangement, in which most passerine species were divided into a few broad groups, like warblers, finches, ovenbirds, or antbirds, based largely on morphology and ecological adaptations. However, recent DNA studies have dramatically changed the understanding of passerine evolutionary relationships, and The Largest Avian Radiation describes our present understanding of the extraordinary historical diversification of passerines and traces their dispersal across the globe beginning some 90-or-so million years ago. It also presents and explains the new classification, which reflects the phylogenetic history.

As demonstrated in the book, new insights have revealed that many of the old evolutionary lineages comprise only a few species that remained in their area of origin (e.g. Acanthisittidae, the New Zealand wrens) or underwent limited dispersal. Only a small number of groups underwent significant proliferation of new species and just five (of 145) passerine families are represented on all continents but Antarctica (e.g Turdidae, the thrushes, and Corvidae, the crows). Even so, the global variation in species richness generally correlates well with the variation in productivity across different environments.

The book documents how a seemingly constant overall rate of evolution of new species is possible because of rapid proliferation in new ecological niches, including archipelagos, and an extraordinary accumulation of endemic species in certain tropical mountain ranges, such as the Andes or highlands of New Guinea. In addition to describing the revised evolutionary history of passerine birds, the authors try to identify adaptational changes, including shifts in life history strategies that triggered major evolutionary expansions. Whilst some families hold only a single species (e.g Rhagologidae, comprising only Mottled Whistler Rhagologus leucostigma; Pityriasidae, Bornean Bristlehead Pityriasis gymnocephala; and Tichodromidae, Wallcreeper Tichodroma muraria), others are highly diverse, comprising nested groups with large numbers of closely related species (e.g Furnariidae, the horneros, foliage-gleaners and spinetails, with c.232 species; Zosteropidae, the white-eyes, with at least 124 species; and Thraupidae, the tanagers, with at least 360 species).

The introductory part of this book is comprised of a number of short chapters that describe the origin of modern birds and their expansion, the reasons why passerines have been so successful, and what is special about them. This is accompanied by an explanation of why traditional taxonomies were full of errors and required updating, and the methodology that has been used to do this. The bulk of the book that follows, around 250 pages, describe the classification, diversity, and relationships of the families that make up the passerines. Each chapter in this part of the book deals with a distinctive group within the passerines (e.g. the suboscine passerines, cohort Corvides, and the superfamily sylvioidea), describing, for example, characteristic morphological and anatomical features, ecological niches and distribution, diet, diversity, and phylogenetic relationships.

These relationships are also revealed in a linear graphical form, so one can see which genera are most closely related, as well as gain an impression of how long ago such genera evolved. Numerous maps are provided to illustrate the global distribution of these closely related species, and the book is illustrated throughout with hundreds of paintings of birds, often along with an appropriate habitat backdrop or depicting some interesting aspect of ecology or behaviour. All of the illustrations have been lovingly painted by Jon Fjeldså, who is not only an editor and author of this work, but also a highly accomplished artist. He also illustrated the wonderful Birds of the High Andes, a field guide that I have had the pleasure using in all of the countries of western South America.

Subsequent chapters cover various topics, but the one I found most interesting was “How New Species Evolve”. In 53 pages, these five chapters cover diverse topics including a discussion of species richness and spatial scale, hotspots of endemism in stable environments, the role of adaptive radiation, and “Anthropocene scenarios”: will biodiversity cradles of the past also maintain biodiversity in the future? A good question, in this age of biodiversity crisis and the Climate Emergency. There are also two detailed Appendices, one being a rather captivating explanation of “A Short Earth History: how the earth changed during the era of passerine birds”, and the other, not to be overlooked, is “An Updated Chronology of Passerine Birds”.

Although the book is undoubtedly most useful to scientists and students of natural history, The Largest Avian Radiation: The Evolution of Perching Birds, or the Order Passeriformes is also intended as a resource for anyone interested in learning about the latest findings relating to global bird diversity and the relationships between the 147 families of passerine birds. Scientists are often not the best people to articulate and disseminate the results of their research to the general public, especially because it is impossible to avoid the use of appropriate, unfamiliar terminology, so many readers will find themselves regularly using the glossary. Nevertheless, this is a meticulous, beautifully illustrated insight into the wonderful diversity of passerine birds, and not only an excellent source of reference, but also the kind of book that one can delve into at any time to discover more about any particular passerines group that one happens to be interested in. Considering the enormous amount of work that has clearly gone into producing it, this fascinating book is an excellent value for the money, and a handy companion to many of the other bird books that you probably already have on your shelves.

– Reviewed by Frank Lambert

A wonderfully well-written and inspiring review; excellent in every way.