Reviewed by Grant McCreary on May 25th, 2014.

When I first saw The Crossley ID Guide, I was blown away by the full-page, unique, photographic plates. I immediately wanted to use it to study some rare birds that I’ve never seen. But I found that these birds were only given a quarter of a page, so small that you could barely make out some of the birds in the image! But at least they are there – many field guides don’t include such birds at all. I get it, though. There are many more people who will be using these guides to look up Setophaga warblers than Phylloscopus warblers. But how about, just once, a field guide that focuses on these rare and vagrant birds that make birders’ hearts, and then their cars, race? A guide for those incurable hopefuls looking for birds that aren’t supposed to be there. A guide like Rare Birds of North America.

Rare Birds of North America is not a field guide, but rather a supplemental guide that will help birders to identify – and find! – rare birds. It covers 262 species that are, well, rare for North America. But what does that mean? For the purposes of this book, a rare bird is not one that is endangered, but rather a vagrant, one “for which, on average, only 5 or fewer individuals have been found annually in North America since around 1950.” If that sounds a little arbitrary, it’s because it is. But the authors had to set some limits, and these are reasonable. It’s not a hard-and-fast rule, though, as some irruptive species and regular migrants on remote Alaskan islands are still included even if they don’t meet this criterion. “North America” here is the United States and Canada, including St. Pierre et Miquelon and excluding Hawaii – basically, the ABA Area.

Species selection is going to be the most contentious thing about this book. Some rarities, like Barnacle Goose and White-faced Storm-Petrel, aren’t included because they are being reported much more often relatively recently, even though they meet the selection criteria across the entire period. No birds that breed annually in continental North America are included, even though some – like the Bluethroat – would be a stop-the-press kind of rarity just about anywhere in this region. Non-migratory birds whose range may be expanding or contracting along the boundaries of the region are also not included (Buff-collared Nightjar, Brown Jay, and the like). Also, it’s worth noting that rare subspecies (such as the Eurasian forms of White-winged Scoter and Herring Gull) are not included. This is particularly disappointing because these could easily be elevated to species status in the future. However, the authors note that adequate data wasn’t available for these, so the same level of analysis wasn’t possible.

While you could easily argue about which species were or were not included, it’s much harder to find fault with the species accounts. They include:

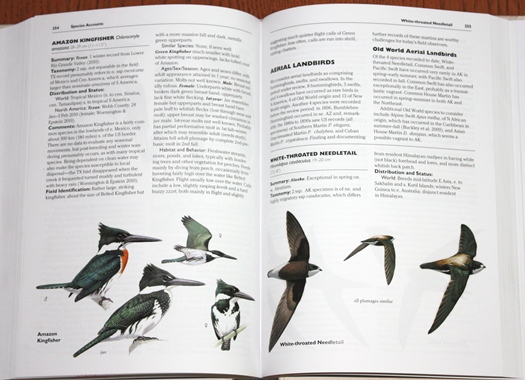

- Header – species name and measurements (length and, for some, wingspan)

- Summary – where and when it occurs in NA, in general

- Taxonomy – total number of subspecies worldwide; discussion of all subspecies that have occurred here; alternative names

- Distribution and Status – summary of world range; detailed description of occurrence in NA

- Comments – the authors’ thoughts and conclusions based on the species’ vagrancy pattern

- Field Identification – overview; similar species; breakdown by age/sex/season; habitat and behavior (including vocalizations)

- Illustrations

The one-half to two-and-a-half pages of text for each species is extremely informative. The Field Identification section has just about everything you’ll need to identify the bird (along with the illustrations). But before you can identify it you first have to find it. The Distribution and Status and Comments sections can help you do just that by isolating where and when the species is likely to turn up.

Rare Birds is great for reference and study, but I’ve enjoyed simply browsing through these accounts, with the Comments being especially interesting reading. These are birds with which I’m not very familiar. In fact, I counted only six that I’ve seen in the ABA area (and around two dozen more elsewhere). But I certainly know these names, having read with envy reports of these birds, and I’ve appreciated making them more than just names to me by reading about them here. I’ve learned a great deal in the process, such as:

- Three out of the four Jack Snipes found in the Lower 48 have been shot by hunters, two by the same person!

- Speaking of Jack Snipe, now I know that if I see a snipe that is appreciably smaller, has streaked (rather than barred) flanks, and/or has a peculiar bouncing action when feeding that I should pay close attention to it.

- There’s an exceptional record of Yellow-browed Warbler in Wisconsin (!!) that, according to the authors, “may represent the tip of the iceberg in terms of Asian vagrants that pass east into the vastness of continental N America every fall but are undetected.”

The only other thing I’d like to have here is range maps. Yes, the range is described, in broad strokes, in the text. But a detailed map showing both the worldwide range and occurrences in NA would have been greatly appreciated.

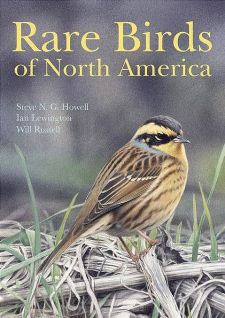

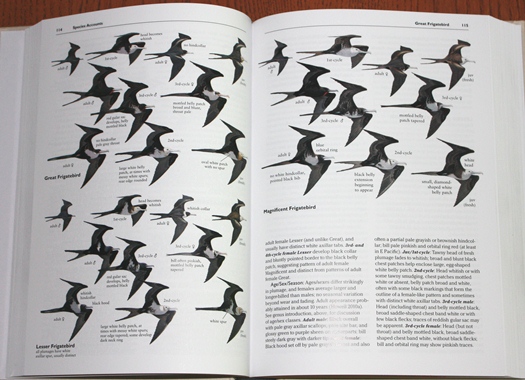

The illustrations by Ian Lewington are reason enough to get this book. They’re gorgeous. The book’s format also allows many more illustrations, and at a larger size, than standard field guides. Each bird has 2-12 illustrations, with most having 3-6. Key variation – by age, sex, season – is depicted and many (especially non-passerines) are shown in flight. What I especially appreciate is that while the main illustrations are the standard field guide pose – birds in profile, all facing the same direction – other angles and different postures are also presented, the better to show off all relevant field marks. Plus, similar species are often shown alongside, such as Great Blue with Gray Heron and Least Sandpiper with Long-toed Stint.

If you don’t recognize the name, Lewington has provided illustrations for several field guides, most notably – and coincidentally – Rare Birds of Britain and Europe. He’s also illustrating a forthcoming full field guide to North American birds to be published by Princeton sometime in the next few years (I can’t wait!).

Looking through Rare Birds you’ll soon notice that the species are in a different order than you’re used to. Overall, the sequencing scheme proposed by Howell et al. is used, whereby birds are grouped into waterbirds and landbirds and then into categories like waterfowl, wading birds, and songbirds. The goal is to present species in a standard order that won’t change with taxonomic updates and to group similar families to facilitate identification. The latter isn’t applicable here, with the limited number of species covered, and the former is also less of an issue here than in full field guides. Still, I’m amenable to the use of this organization here. More bizarre is splitting up species within each of these categories based on their origin, either from the old world or new world. All the old world songbirds are presented before any from the new, which means that, for instance, Eyebrowed Thrush is separated from Rufous-backed Thrush by 72 pages. I’m not sure why this was done, but it does allow the authors to include a short introduction to each grouping summarizing the vagrancy patterns displayed. This makes it harder to find some birds, at least initially. But once you get used to it it’s not a big deal.

The 41-page introduction is worth reading, especially for a discussion on general causes of vagrancy and an analysis on where vagrants to NA come from and how they get here. There’s also an overview of bird topography, molt, and aging that’s a good introduction or refresher on the topic. An appendix contains three species that were new to NA as the book was being prepared. The second appendix on Species of Hypothetical Occurrence is fascinating reading. From a Humbolt Penguin caught in a net off Alaska to a Rufous-collared Sparrow in Colorado, these are birds that are not generally accepted due to questions of identification or provenance. This section is filled with words like “presumed”, highlighting how little we know about many birds.

Recommendation

Anyone who regularly birds one of the states where vagrants routinely show up – Florida, Texas, Arizona, California, or Alaska – absolutely should have Rare Birds of North America handy at all times. But I’d urge any birder in North America who chases rarities or, especially, wants to find one themselves to have this book and study it. It will make you a better, more attuned birder.

Disclosure: I get a small commission for purchases made through links in this post.

Buy from NHBS

(based in the U.K.)

Disclosure: The item reviewed here was a complementary review copy provided by the publisher. But the opinion expressed here is my own, it has not been influenced in any way.

Thanks for sharing your thoughts about rare birds of north america.

Regards