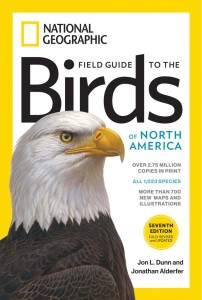

Changes in 7th Edition of National Geographic Field Guide to the Birds of North America

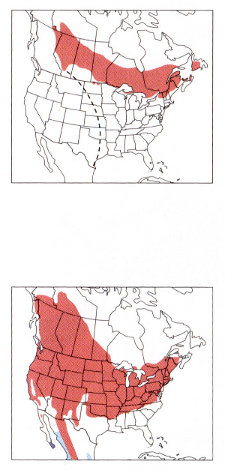

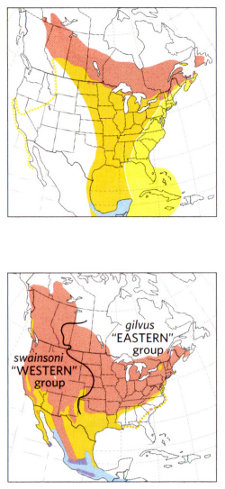

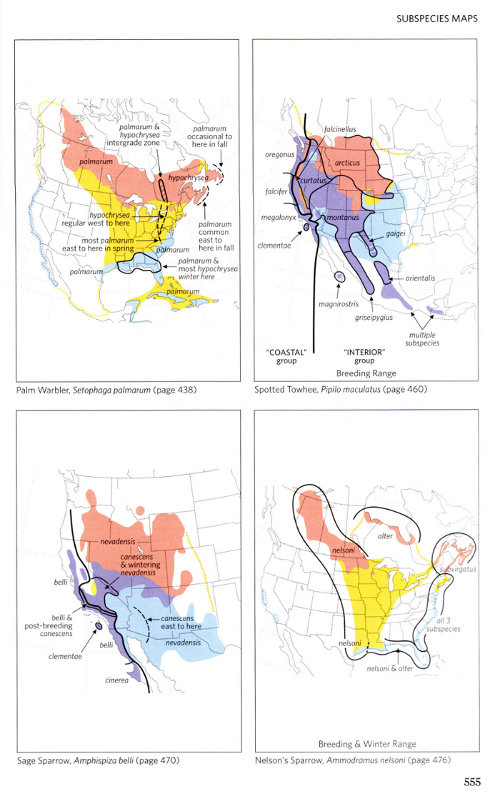

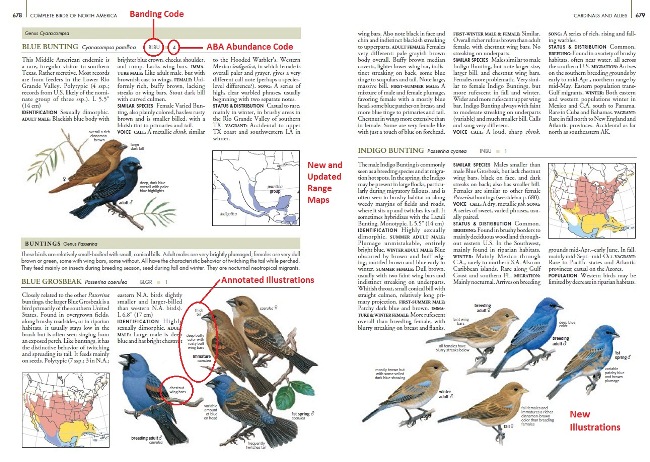

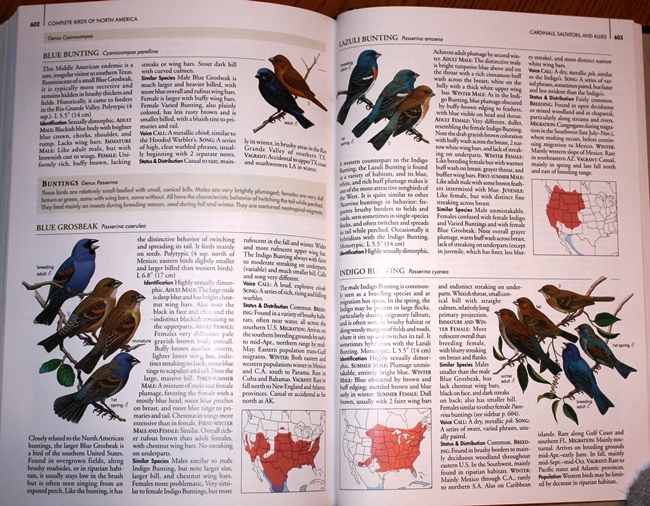

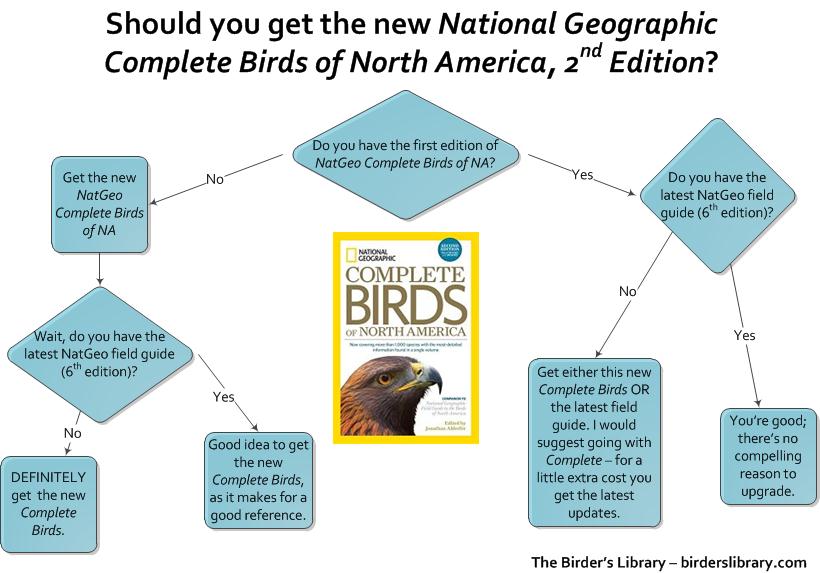

December 22, 2017 | Comments (0) National Geographic recently published a new edition of their popular bird field guide. As always, this new edition incorporates new species (1,023, up from 990) and the latest taxonomic updates (as of 2016), but also has a range of other changes and improvements. Most of these are new, replacement illustrations. In this case, new is improved – these are all definite improvements. The maps have also been extensively updated, with 50+ new range maps (vagrants, i.e. Smew), 16 new subspecies maps, and “hundreds” of updated maps. I’ll offer my thoughts on all of this in my full review. But in the meantime, here are all of the changes to the plates, as best I could tell, whether they be new species, new or replacement illustrations, or changes to the annotated notes.

National Geographic recently published a new edition of their popular bird field guide. As always, this new edition incorporates new species (1,023, up from 990) and the latest taxonomic updates (as of 2016), but also has a range of other changes and improvements. Most of these are new, replacement illustrations. In this case, new is improved – these are all definite improvements. The maps have also been extensively updated, with 50+ new range maps (vagrants, i.e. Smew), 16 new subspecies maps, and “hundreds” of updated maps. I’ll offer my thoughts on all of this in my full review. But in the meantime, here are all of the changes to the plates, as best I could tell, whether they be new species, new or replacement illustrations, or changes to the annotated notes.

- Egyptian Goose – new (moved from Exotic Waterfowl to main section)

- Tundra and Trumpeter Swams – bills of the juveniles are more pink, and Tundra has a new note that there is “extensive pink at base of bill on juvenile”

- “Mexican Duck” – added note that female is similar to male and both lack dark saddle on bill. Nice addition since only the male is illustrated

- American x Eurasian Wigeon hybrid – new

- Harlequin Duck – new notes on female

- Common Merganser – new illustration of the head of displaying “Goosander” adult male

- Swan Goose – addition to Exotic Waterfowl

- Graylag Goose – moved from Exotic Waterfowl to Accidentals section

- Sooty Grouse – new illustrations of displaying male sitkensis and hooting male howardi

- Rock Ptarmigan – new illustration of Attu evermanni summer male

- American Flamingo – new illustrations of Lesser, Greater, and Chilean Flamingos

- Jouanin’s Petrel – new

- Providence Petrel – new

- Zino’s Petrel – new

- Flesh-footed Shearwater – replaced illustration; added illustrations of one taking off and one sitting on water (with comparison to Heermann’s Gull)

- Manx Shearwater – in-flight top view illustration replaced; one of the in-flight bottom views removed

- Audubon’s Shearwater – both in-flight illustrations replaced; added 2 illustrations of birds on the water

- Barolo Shearwater – split from Little Shearwater. Previous illustrations of Little replaced; added bird on the water

- Nazca Booby – new

- Tricolored Heron – new illustration of in-flight breeding adult (very needed addition)

- Little Blue Heron – new illustration of in-flight adult

- Green Heron – replaced in-flight illustration

- Osprey – new illustration of ridgwayi

- Mississippi Kite – in-flight illustrations have been replaced and an in-flight 1st summer added

- Swainson’s Hawk – in-flight illustrations have been replaced and an in-flight juvenile added

- White-tailed Hawk – added in-flight 2nd year

- Ferruginous Hawk – replaced in-flight adults and juvenile

- Rough-legged Hawk – replaced in-flight adults, and totally new annotations

- American Kestrel – added in-flight female

- Prairie Falcon – replaced in-flight image

- Peregrine Falcon – replaced in-flight adult, added in-flight juvenile

- Gyrfalcon – replaced in-flight image

- Limpkin – added in-flight

- Yellow Rail – replaced in-flight image

- Black Rail – replaced image

- Sora – added in-flight juvenile

- Corn Crake – added in-flight

- Ridgway’s Rail – added Bay Area obsoletus

- Clapper Rail – added worn adult

- Common Gallinule – replaced the breeding and juvenile images, added inset of the head of Eurasian Moorhen adult breeding

- Sandhill Crane – replaced in-flight image

- Common Crane – replaced in-flight image

- Little Gull – juvenile added

- Bonaparte’s Gull – juvenile added

- Franklin’s Gull – juvenile added

- Heermann’s Gull – juvenile added

- Yellow-legged Gull – added 2nd winter

- Bridled / Sooty Terns – added detailed comparison of adult heads

- Caspian Tern – juvenile added

- Elegant Tern – juvenile added

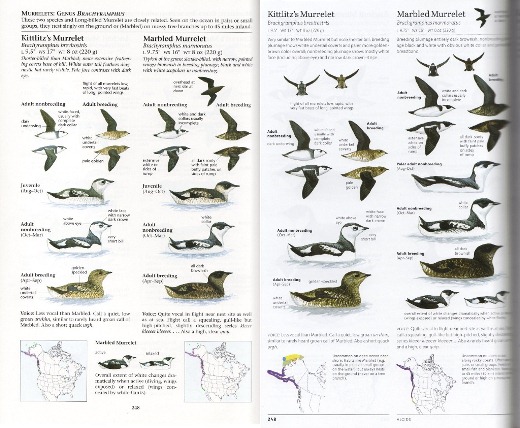

- Common Murre – winter replaced, juvenile removed

- Pigeon Guillemot – in-flight winter adult replaced (mislabeled as breeding in 6th ed.); breeding adult in flight added

- Cassin’s Auklet – both illustrations replaced

- Ancient Murrelet – all illustrations replaced

- Guadalupe / Scripps’s / Craveri’s Murrelets – all illustrations replaced and new ones, such as close-ups of heads, added

- Atlantic Puffin – in-flight replaced

- Band-tailed Pigeon – juvenile (head-only) added

- Common Ground-dove – all illustrations replaced, with new ones added

- Ruddy Ground-dove – all illustrations replaced, with new ones added

- Ruddy Quail-dove – both images replaced

- Greater Roadrunner – image replaced, in-flight illustration added

- Long-eared Owl – added in-flight and Eurasian otus ssp

- Short-eared Owl – added illustration of domingensis (Carribean ssp)

- Northern Saw-whet Owl – added brooksi ssp

- Common Pauraque – replaced both sitting and in-flight birds

- Mexican Whip-poor-will – replaced image

- Elegant Trogon – juvenile added

- Hummingbirds – ALL replaced (except for Lucifer) and many new images and details added

- American Three-toed Woodpecker – Rocky Mountain male replaced with a female

- Northern Flicker – added image of intergrade male Red-shafted x Yellow-shafted

- Pine Flycatcher – new species

- Eastern Kingbird – adult and in-flight replaced, juvenile missing

- Thick-billed Kingbird – both images replaced

- Great Kiskadee – perched bird replaced

- White-eyed Vireo – inset of an immature added

- Blue-headed Vireo – replaced, added female

- Cassin’s / Plumbeous / Gray Vireo – all replaced

- Yellow-green Vireo – replaced, immature added

- Black-whiskered Vireo – replaced, added altiloquus

- Blue Jay – added in-flight

- Florida Scrub-jay – image replaced

- Yellow-billed Magpie – added juvenile

- Purple Martin – all images replaced except for western female in flight

- Northern Rough-winged Swallow – all illustrations replaced

- Bank Swallow – all illustrations replaced

- White-breasted Nuthatch – images replaced, added male aculeate

- Rock Wren – replaced

- Cactus Wren – added saniegensis

- Winter Wren – illustration darkened

- Sinaloa Wren – added (moved from Accidental section)

- Blue-gray Gnatcatcher – added female obscura

- Willow Warbler – added fall illustration

- Artic Warbler – fall xanthodryas removed (7th ed. Informs us that ssp is now split as Japanese Leaf Warbler, which is unrecorded in N.A.)

- Common Chiffchaff – added

- Wood Warbler and Pallas’s Leaf Warbler – added (moved from Accidental section)

- Bluebirds – all lightened up

- Aztec Thrush – all replaced

- Gray Catbird – lightened

- Blue Mockingbird – lightened a bit

- Brown / Long-billed Thrasher – both replaced

- Common Myna – added in-flight

- Eastern Yellow Wagtail – removed juvenile

- White Wagtail – added breeding male alba

- Bohemian Waxwing – adut replaced, added centralasiae and in-flight

- Cedar Waxwing – added in-flight

- Lonspurs – added wing tip detail for each species

- Magnolia Warbler – all replaced

- Black-throated Gray Warbler – added immature female

- Cerulean Warbler – added fall immature male

- Red-legged Honeycreeper – new

- Rufous-crowned Sparrow – the interior and coastal adults have been replaced, southwestern scottii added, and juvenile image retained, but darkened a little

- Field Sparrow – all illustrations replaced

- Bell’s / Sagebrush Sparrows – added illustrations of outer tail feathers

- Fox Sparrow – all replaced except for “Red” (which was new in 6th), “Sooty” townsendi added

- Pine Bunting – new (moved from Accidentals and added female and breeding male)

- Yellow-browed Bunting – new (moved from Accidentals and added spring male)

- Yellow-throated Bunting – new (moved from Accidentals and added female)

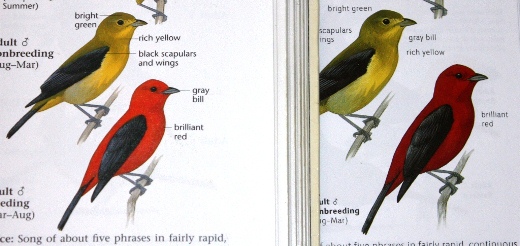

- Flame-colored x Western Tanager hybrid – new

- Red-winged Blackbird – the 3 female images are replaced

- Tricolored Blackbird – female replaced

- Orchard Oriole – breeding male fuertesi added

- Brown-capped Rosy-finch – male replaced

- Pine Siskin – added green morph

- Hawfinch – breeding male replaced, fall/winter female added

- Northern Red Bishop – (renamed from Orange Bishop) female replaced

- Pin-tailed Whydah – new

- Bronze Mannikin – new

- Tricolored Munia – new

The Warbler Guide

The Warbler Guide

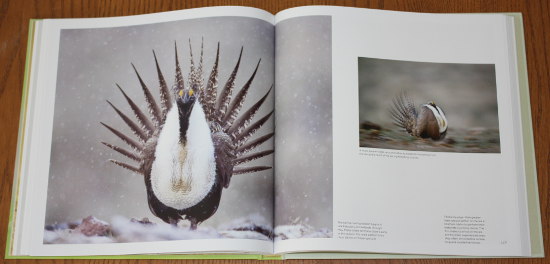

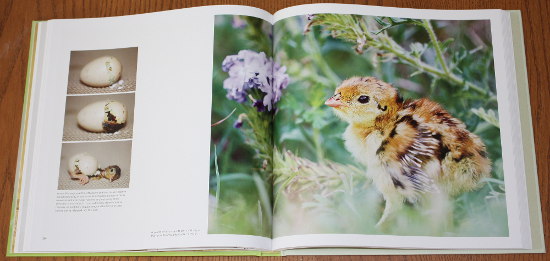

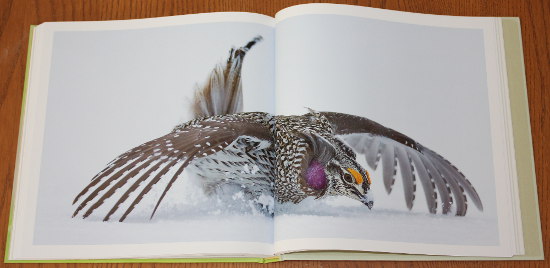

Save the Last Dance: A Story of North American Grassland Grouse

Save the Last Dance: A Story of North American Grassland Grouse

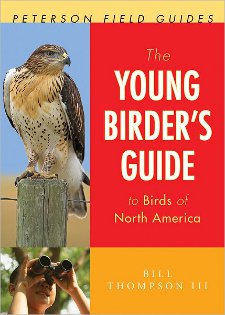

The Young Birder’s Guide to Birds of North America

The Young Birder’s Guide to Birds of North America