Reviewed by Grant McCreary on April 27th, 2016.

Back in 2011, I reviewed Atlas of Rare Birds, a book by Dominic Couzens that profiles 50 endangered birds. I have always fancied stories about rare birds, but one in particular here caught my eye. It was the photograph. Every profile in the book included one or more illustration of the bird. But not this one; all it had was a photo of a single, detached wing. That’s because that was all that was known about the bird.

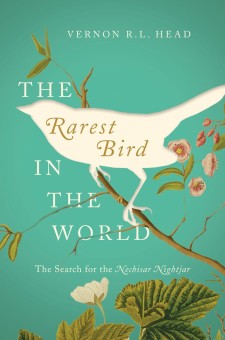

In 1990, a team of ornithologists was surveying Nechisar National Park in southern Ethiopia. During a night drive they found a road-killed nightjar. It was badly decomposed, so all they were able to salvage was the wing. When they later tried to identify it, to their surprise they found they could not match it up to any species in the area or, indeed, with any known nightjar in the world. It was a new species, which they named Nechisar Nightjar. Couzens goes on to say that for about 20 years since the discovery no further proof of the bird’s existence had been forthcoming. That changed in 2009, when a team of four birders claimed to have seen it alive. Wow! Incredible story, but I needed more details. What was it like to go searching for a true ghost bird? Did they actually see the bird? I had no way of finding out. That is, until one of those four birders, Vernon Head, chronicled the trip in The Rarest Bird in the World: The Search for the Nechisar Nightjar.

As Head vividly describes, searching for this bird isn’t like the birding that most of us are used to. They had to hire a driver and load up on supplies, as the plains this nightjar is supposed to inhabit are far from anything else. After a long journey, the intrepid foursome found themselves at Nechisar National Park…only to be greeted by a man brandishing an automatic rifle. Driving onto the plain at night, their only chance to find the bird, is actually against local law. Their driver/interpreter, after a few tense minutes, was able to convince the guard to let them continue. This saved the trip, as there was no backup plan: they had to drive through the reserve at night and “entering without a permit might have meant death.”

The group camped the first night, and spent the next day driving deeper into the park where the wing had been found. You can imagine the anticipation they must have felt while waiting for night to fall. But at least they had some incredible birds to watch in the meantime, albeit ones that had been known to science for much longer than ten years. At night, they loaded into their vehicle, armed with searchlights, and set off to find a living, breathing Nechisar Nightjar. Their plan was to catch one, using a special searchlight. Then, “the prize would then be viewed, photographed and hastily released back into the night, unharmed.” Ornithologists would do the same, except they would kill the bird first so as to have a complete specimen. Head didn’t explain why they did not go that route, but I assume it’s because they lacked the necessary permits and, more importantly, didn’t want to kill what truly could be one of the rarest birds in the world.

If you’d prefer not to find out whether or not the team found the bird, skip until after ‘END SPOILERS’ below. The spoiler text should be hidden, but if for some reason it’s not, just avert your eyes until that section is passed. If you’d like to continue reading, simply click Expand below.

******** BEGIN SPOILERS ********

******** END SPOILERS ********

While the words Nechisar Nightjar in the book’s subtitle leapt out at me – as I said, I’ve been fascinated by this bird ever since first reading about it – the main title wasn’t that far behind. Can you truly call this bird “the rarest bird in the world”? After all, there are at least two other books, each dealing with different birds, all purporting to be about the world’s rarest bird*. Somewhat surprisingly, the author tackles this question head on (pun intended, I couldn’t help it!). He devotes an entire chapter to the concept of ‘rarity’ in the natural world. In the process of determining which bird is the rarest, he considers – and rejects – a number of candidates before ultimately settling on the Nechisar Nightjar. Some of these candidates are ones that would immediately come to mind in such a debate, such as Ivory-billed Woodpecker and Spix’s Macaw. Others, like Sidamo Lark and White-chested Tinkerbird, are much more obscure. Whether or not you agree with Head’s reasoning in determining the champion, this is a thought-provoking read.

But, as interesting as the chapter is, it is an aside to the main story. And it’s not the only one; Head also sidetracks to discuss, among other topics, the nightjar family as a whole and how he met each of his companions. Whether these digressions enhance or detract from the book as a whole has to be decided by each reader. Personally, I found them at least mildly interesting, with some, especially the discussion on rarity, being particularly thoughtful or entertaining. But I can’t help but feeling that they are, at least somewhat, filler. This is a fairly short book to begin with, so if you remove the parts completely unrelated to the main narrative it may become unpublishable.

Birding in remote Africa looking for a bird that no one (at least no one outside of the local inhabitants, presumably) has seen alive. That’s about as interesting as it can get, at least to me. Even so, I had trouble reading The Rarest Bird in the World for an extended period of time. The prose goes beyond purple into the ultraviolet range, with a simile lurking in seemingly every sentence. These flourishes aren’t horrible in and of themselves, even the most unnecessary ones have some cleverness that you can appreciate. For example, “our vehicle awaited us, shivering like a naked boy about to step into a bath.” But many are completely unnecessary and the sheer number of them assaults you, making it tough to read much of this book at a time.

I rarely comment on a book’s cover, but have to this time. It’s attractive, with a bird “cut out” of a painting, but it doesn’t really fit the subject matter. First, the silhouette is clearly not one of a nightjar. Ok, that may be looking at it too literally. Second, I was about to say that this cover would work much better for a book on extinct birds, but realized that The Ghost with Trembling Wings, a book on that precise subject published over a decade ago, has essentially the same cover. So, perhaps this wasn’t a good cover choice after all.

Recommendation

The Rarest Bird in the World: The Search for the Nechisar Nightjar tells of a bird that was discovered in a most improbable manner and the quest to see it living for the first time. It’s an amazing story, one worth reading. But it would have been more enjoyable had the author exercised a little more restraint on the flowery language.

For more details on these events, the Wall Street Journal has an interesting interview with Vernon Head.

Note: the edition reviewed here is the first published in North America (2016). However, it was originally published by Signal Books in 2014 (with a much more appropriate cover!).

* Those other books are:

Disclosure: I get a small commission for purchases made through links in this post.

Buy from NHBS

(based in the U.K.)

Disclosure: The item reviewed here was a complementary review copy provided by the publisher. But the opinion expressed here is my own, it has not been influenced in any way.

[…] The Birder’s Library […]