Reviewed by Grant McCreary on January 23rd, 2016.

John James Audubon was incredibly innovative. Many are aware of his bird portraits, and not just fans of birds or American art, for his work seems to be all over the place. But what you can’t tell by looking at his work reproduced in books, hanging on a wall, or slapped on any other random object is that he depicted every bird life-sized. To truly appreciate this, you have to view the original prints or, better yet, his original watercolors. The scale makes as much of an impact as the life-like, often outlandish, postures Audubon portrayed.

There have been others to illustrate birds life-sized, of course. Just recently, Hummingbirds: A Life-Size Guide to Every Species showed almost every hummingbird in full size. But hummingbirds are tiny, it’s hard to do the same for a wide range of birds. But Life-size Birds: The Big Book of North American Birds has attempted to do just that.

This book includes a wide variety of birds, with each having at least one full-size, 1:1 picture. Unsurprisingly, it is fairly large book at 12.25×14.25 inches (31×36 cm). (Although not nearly as large as Audubon’s folios.) Even so, it’s clearly not big enough to show larger birds in their entirety. In order to include such birds as the Bald Eagle and Great Blue Heron, something different had to be done. For these larger birds, it shows just the head and as much of the rest of the bird as the page size allows. In many cases, some smaller scale photos (i.e. 1:2 or 1:4) are also included in order to show the entire bird or to incorporate a wider variety of shots.

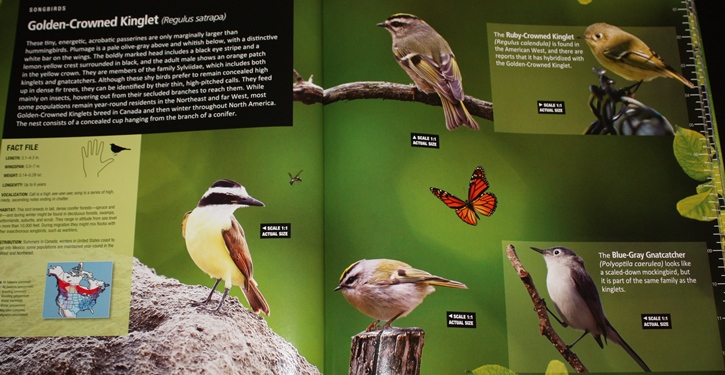

Each species has its own two-page spread, sometimes shared with one or two inserts of a similar bird. The accounts include a surprising amount of interesting material, starting with an introduction that describes the bird and gives pertinent facts such as diet, habits, and breeding. A “Fact File” box provides further information on length, wingspan, weight, longevity, vocalization, habitat, and distribution. A range map rounds out the account.

A wide variety of species are included. You have popular birds that one would expect, such as Northern Cardinal, Blue Jay, and various raptors and ducks. But they are joined by birds that are known pretty much only to birders: Cassin’s Auklet, California Gnatcatcher, Sagebrush Sparrow, Virginia Rail, and some shorebirds. I was shocked, in a very good way, to see some of these included.

Life-size Birds is a visually striking book. I suppose that’s not hard when you have full-sized birds gracing the pages, such as three male Scarlet Tanagers in their glorious red-and-black plumage just waiting to cause oh-so-sweet retina damage. But these are bright, colorful pages even without the birds. The composite images include the birds and some elements of their habitat, such as branches to perch on. Insects – bees, butterflies, and other flying bugs – have been added to many images. Some are very natural-looking, but most distractingly stand out as obviously photoshopped, such as the exact same Monarch butterfly that shows up on multiple pages. The backgrounds are highly blurred and tinted a color – usually green, but sometimes purple or orange. Tick marks, measuring in inches, edge the outside of the pages, providing a sense of scale. Most pages are framed with leaves, as if you’re looking through them to see the bird.

These composite images work well, for the most part, but have some glaring issues. As previously mentioned, they are colorful, arresting, and often beautiful. They aren’t very busy, which is good because at this scale that would be way too distracting. The leaves around the edge work great for the songbirds, so much so that at first I didn’t even notice that they were, for the most part, exactly the same from page to page. But this scheme is used for some wildly inappropriate species.

For instance, the Black Oystercatchers here are striking. Or rather, they would be without the leaves around the page edges. Has this bird ever shared a binocular view with even a single leaf? Ok, maybe that’s an exaggeration. Still, they are out of place. As is the green background, further suggestive of a forested habitat. It should instead be the gray or blue of their rocky, seaside haunts. I thought that plate was bad, until I discovered that the same thing was done to the Wilson’s Storm-Petrel! I have to give props for even including a storm-petrel in a book like this, but seeing them juxtaposed with leaves is just plain wrong.

So, are these life-sized birds anything other than a gimmick? In the introduction, the author states:

This book is meant as a handy identification guide to a variety of North American species and also a way to furnish images of the birds at their actual size. Novelty factor aside, it will give birders a means of comparison to other, similar birds, as well as offering a sense of the diminutive aspect of favorite songbirds and the startling size of some predators, waterbirds, and waders, many of which bird lovers rarely have the chance to see at close range.

“Handy identification guide” this is not. Yes, I’m sure that some birds will be identified after seeing them on these pages. But, as wide as the species selection is, it is not deep, covering 95 birds (plus a handful of others shown as comparisons). And being able to compare the size of various birds on these pages is not going to realistically help any birder. The point about offering a sense of just how big, or small, some of these birds are is valid, though. Indeed, the first thing that struck me is that these birds looked so big like this, as opposed to through binoculars.

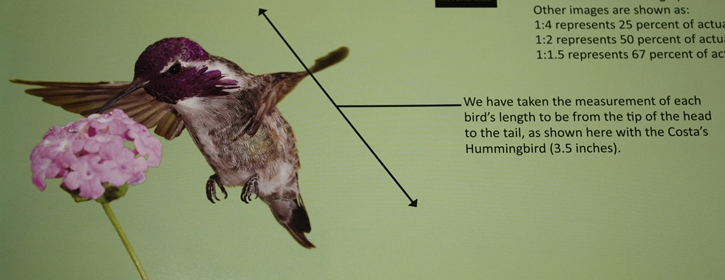

Well, it turns out that some of the birds on these pages may truly be too big. The book informs us that the size measurements used are from the “tip of the head to the tail”. But the measurements in the book roughly match to those in the Sibley Guide, which are measured from bill tip to tail tip. See the below image of a Costa’s Hummingbird, used as an example in the introduction.

The line on the page, spanning the length of the bird from the top of the head to the tail, is 3.5 inches. And 3.5 inches is, indeed, a good approximation of the length of a Costa’s, but from the tip of the bill to the tail. Thus, the Costa’s here is actually greater than life-sized. Likewise, Life-size Birds’ Calliope Hummingbird is five inches from bill to tail tip, or about one-and-a-half times larger than it should be (3.25 inches). Similarly, two male Bobwhites, both purported to be actual size, are clearly different sizes on these pages. I am aware that it must be exceedingly difficult to accurately scale photographs of birds in various postures taken from angles that do not allow direct measurements. So the occasional misjudgment of size is easily forgiven. But the entire basis for the scaling used in this book is fundamentally flawed, which raises doubt on the accuracy of all the images contained within it. Now, when I look at the Northern Mockingbird on these pages, does it seem so large because it truly is, or because the scale is off?

If that were the only issue of Life-size Birds, it would be grievous, but not fatal. However, I find some sort of error almost every time I open the book. A few are, admittedly, minor copy issues, such as “warbler” instead of “sparrow” deep within a block of text. But I have found nine misidentified birds. In one case, I believe the label is incorrect – a Spotted Towhee is shown as a comparison against the Eastern, but it is labeled as another Eastern. But in others, the wrong bird is shown. Some are somewhat understandable because the species look very much alike, such as the purported male Barrow’s Goldeneye that looks to me like a Common Goldeneye, or a photo of a Great Egret being used instead of the intended white-morph Great Blue Heron. But for some of these, I have to shake my head in disbelief. In a sidebar meant to show the resemblance of Turkey Vultures to Wild Turkeys, instead of a Turkey Vulture head we find instead a King Vulture. Somehow, a female Red-winged Blackbird is shown instead of the expected female Purple Martin. And, the granddaddy of them all, the two pages of Golden-crowned Kinglets show three of the birds in actual size. Except, one of them is a Great Kiskadee!! Seeing a large, hulking kiskadee scaled down to match the diminutive kinglets makes me laugh. Which is good, because otherwise I’d be crying.

If it seems like I’m coming down hard on this book, it’s not because it’s worthless and should never have been published (if that was the case, I wouldn’t even bother reviewing it). On the contrary, Life-size Birds had great potential. Birders won’t find much new here, other than the novelty. But those who are perhaps slightly interested in birds, especially younger readers, could find in these large, gorgeous pages a gateway to a wider world of birds in all their fascinating diversity. My kids (aged six and four) greatly enjoyed looking through it with me. The large photographs really caught their attention.

It’s worth pointing out that all of this could easily have been avoided. Please, if you are writing or publishing a bird book, have it reviewed by someone who really knows birds before putting it out there.

Recommendation

Life-size Birds: The Big Book of North American Birds is a wonderful concept that had great potential to ignite an interest in birds. It does many things right – it is a visual treat and includes a wide variety of birds. Unfortunately, errors are rampant. It could still serve its intended purpose; personally, I plan on keeping it available near the windows overlooking our birdfeeders so that my kids can peruse it. But I would only recommend doing so if there is someone around who can point out the mistakes.

Disclosure: I get a small commission for purchases made through links in this post.

Buy from NHBS

(based in the U.K.)

Disclosure: The item reviewed here was a complementary review copy provided by the publisher. But the opinion expressed here is my own, it has not been influenced in any way.

[…] The Birder’s Library […]