Reviewed by Grant McCreary on June 17th, 2008.

In 1977, the National Audubon Society published the first field guide to North American birds that exclusively used photographs. As Tero said on BirdForum, “We have come a long way since (then)”. This guide, along with a few others published in the last decade, has elevated the photographic field guide far beyond its humble beginning.

Photographs

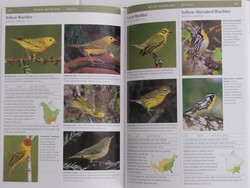

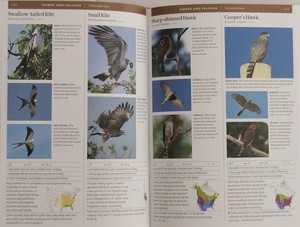

Let’s jump straight to the most important part of the book – the photographs. For the most part, they do not disappoint. They are sharp and in focus, and present the species against a natural background. In other words, they look very nice. (Please note that any grain or other imperfections in the photos included in this review are in my pictures, and not the book itself.)

Each species gets approximately three photographs, with a minimum of one and maximum of 10. The photographs vary in size depending on the page layout. However, the layout is very flexible, which allows each photograph to be as large as it can possibly be, given all the information packed onto these pages.

Each species gets approximately three photographs, with a minimum of one and maximum of 10. The photographs vary in size depending on the page layout. However, the layout is very flexible, which allows each photograph to be as large as it can possibly be, given all the information packed onto these pages.

Each photo includes a caption that highlights the most prominent field marks for the species, as well as other important information. This is often the only “traditional” identification-related text, so reading them is crucial. Additionally, each picture is labeled with the state/province and month in which it was taken. This ought to be a standard feature for any photography-based guide, as species can vary greatly based upon location and time.

One of the main shortcomings of using photographs in field guides is that it is extremely difficult for a single photo to show most of the bird, and more importantly, all relevant field marks. It is obvious that the author has attempted to combat this problem through careful photograph selection and the use of multiple pictures for the majority of species. For instance, two examples of Magnolia Warbler are included, a breeding male and an immature. One of the best field marks of this species, especially during the fall, is the black-tipped tail. The immature’s photo does not show this, but it is mentioned in the caption. However, the picture of the male shows off this feature very nicely. Many of the photographs here work together in such a way. Still, it is impossible to mention, much less depict, all relevant field marks, and this guide is no exception.

Another relative weakness of photographic field guides to those using paintings is the number of illustrations. Photographs simply take up more space. And that is certainly the case here. The number of pictures per species in this guide is less than in the National Geographic and Sibley guides. Nevertheless, it does compare favorably to other recent photographic guides, and the majority of species are still covered adequately. But there are some that could use more coverage, such as the swallows, where surprisingly three of the eight are not shown in flight.

Species Accounts

The accounts are included on the same page as the photos. On average, there are about two accounts per page. Each of these includes:

- Name – common and scientific

- Abundance code – uses the ABA code system

- Size – length, wingspan, and weight

- Variation – including molt, age, sex, seasonal, and more

- Habits and ecology

- Voice – description of song, call, and flight call

- Range map – shows breeding, winter, resident, migration, and rare

You may notice that none of these sections deals with identification in the traditional sense. As previously mentioned, that is covered in the photo captions. However, there is some useful information here, rarely included in field guides, that supports the author’s stated goal to emphasize natural variation and “a ‘holistic’ view of the bird as the sum of its behavioral, ecological, and morphological parts”.

The first of these features that the reader may notice is some text next to the species name that gives a code number, such as “Code 1”. This is a numeric code defined by the American Birding Association that classifies the general abundance of all North American birds. The most common are classified as Code 1, with increasing numbers signifying decreasing abundance. Code 6 is the highest, which means the species is extinct or otherwise impossible to see in the wild. This guide covers all birds defined as Code 1, 2, and 3, and gives limited treatment to some Code 4 species (such as Red-tailed Tropicbird). As a new birder, one of the first things that I wanted to know about a bird was how common it was. Until now, the regional Sibley guides were the only ones that consistently provided this information. The use of this code system is inherently generic and not location-specific. However, it is a standardized and succinct way of giving the reader abundance data, and I thus applaud its use here. I hope it becomes a standard.

Variation in species is emphasized through three bullet points in each account: molt; sex, age, and seasonal differences; and other variation. For example, this is what we are told about the variations in American Redstarts:

- two adult molts per year; complex alternate strategy

- strong age-related and sex-related differences

- extent of color variable, especially in subadults

The types of molt strategies are described in the introduction. (As an aside, I was surprised that redstarts molt twice, since adults don’t look any different between spring and fall. I researched further and found that adults do indeed molt twice a year, but the molt in spring (“pre-alternate”) only includes the feathers near the eyes and bill. But now I’m even more curious – why just those feathers?)

The habits and ecology section is the most extensive. It includes information on habitat and behaviors, such as feeding, mating, and nesting. There is some good stuff here that can even potentially help with identification.

Paul Lehman, the undisputed guru of North American bird distribution, contributed the range maps, and they are as good as one would expect. They are very detailed and use a whopping five colors to indicate breeding, winter, resident, migratory, and rare ranges.

The Rest of the Book

Turning back to the beginning of the book, we find a fairly extensive introduction. Of course, there is the obligatory description of the guide and how to use it. Following that is a summary of the natural history of birds, including a survey of various habitats, behavior, migration, topography, etc. For a general field guide the discussion of molt is very extensive. Finally, there is a great section on identification, focusing on topics and ideas not usually treated in field guides. Make sure not to skip it.

The topography diagrams deserve to be mentioned. There are seven in all – a duck, songbird, raptor perched, raptor in flight above and below, gull, and shorebird in flight. For each one there is a photo of a bird and a line drawing that mirrors the photograph. Only the drawing is labeled. This allows the user to practice isolating and naming feather tracts on an actual bird.

There is also an introduction for each bird family. These are given a full page and include an overview of habitat, behavior, diet, population, and conservation status. They also tell how many species of that group occur in NA, broken down by ABA codes. Discussions of a more general nature are also included in some of these intros, especially those for families with few representatives in this area. For instance, the majority of the introductory material for flamingos discusses the general issue of natural vagrancy and escapes from captivity. There are also a few sidebars placed amongst the species accounts that cover topics such as long-distance migration and mobbing. These were a surprising, but welcome, inclusion.

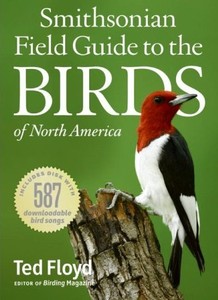

I know this doesn’t count for much, but I have to say that to me, this cover is the most effective and, aside from the blurb about the DVD, most attractive of any NA field guide. You just can’t go wrong with a Red-headed Woodpecker!

The DVD

A unique feature of this guide is that it includes a DVD with “587 downloadable bird songs”. Only 138 species are represented (complete list here), thus it is not extensive enough to be your only source of bird songs. On the other hand, there is an average of over four tracks per species, so you get more variation than other collections provide. The tracks are in MP3 format, and the track name includes a species abbreviation, track number, short description of the vocalization, and, when available, the state/province in which it was recorded. It also comes with a nice booklet listing all of the tracks.

I approve of the choice in format, both of the tracks and the disc itself. It allowed many more tracks to be included than otherwise would be the case. Additionally, most birders today utilize an iPod or other mp3 player to play bird songs. This format allows easy transferring to such devices without any conversion or editing.

The vocalizations on this disc will make a nice supplement to your bird song collection. I hope that an expanded version that includes most North American species is eventually made available, because such a collection would easily be the best on the market.

Recommendation

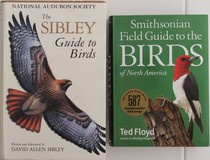

The Smithsonian guide is a little large to fit in most pockets, but would otherwise be a perfectly acceptable primary field guide. But I think its real value is as a reference and photographic compliment to your primary guide. Overall, I consider this the best photographic field guide to North American birds to date.

My only reservation is that it may be a little too advanced for beginning birders. At least I can see how it could have been somewhat confusing for me when I first started out. I would say that the Kaufman guide is probably the best photographic guide for those new to birding.

For a detailed comparison of this and other photographic guides, check out my Field Guide to the Photographic Field Guides of North America.

Also, the book’s home page has more information, including excerpts of the book and even some sample bird sounds from the DVD.

Disclosure: I get a small commission for purchases made through links in this post.

(1 votes, average: 4.00 out of 5)

(1 votes, average: 4.00 out of 5)

I start to reed recently the guide and it is very interesting. My question concerns the immature Sharp-shinned Hawk perched, on page 121 : the fine steaks seem identical to the ones of the immature Cooper’s Hawk. Look at this http://www.birds.cornell.edu/pfw/AboutBirdsandFeeding/accipiterIDtable.htm

Thanks for your answer.

Sincerely,

Raymond Belhumeur

Longueuil, arr.Saint-Hubert

Québec

Canada

raymond.belhumeur@internet.uqam.ca

I see what you mean, Raymond. Cornell, and even Sibley, show the immature Sharp-shinned with “heavy, reddish” streaks. That is, apparently, the “typical” look. But the juv sharpie in the Smithsonian has smaller streaks, they are more brown, and just looks lighter.

With raptor ID questions such as this, I usually turn first to the Wheeler raptor guides. All but one of the immature sharpies in that guide look like the bird on the Cornell site. However, one does look like the Smithsonian. In the text it does say that there is a “narrowly streaked type” of juveniles. The description sounds very much like the bird shown in the Smithsonian.

Thus, it seems like this is a fairly normal appearance. However, since there was room in the Smithsonian for only one pic of the imm sharpie, it’s debatable whether this was an appropriate plumage type to include.

This situation also shows why it’s important that birders have multiple resources for ID.

That was a great catch, and something that I had never before noticed about the accipiters (I don’t see many sharpies perched around here).