Reviewed by Frank Lambert on November 30th, 2019.

This is the first global seabird guide since the 1980s, when Peter Harrison’s classic Seabirds: An Identification Guide (1983, 1985) and Seabirds of the World: A Photographic Guide (1987) were published. There are, of course, other very useful identification guides that focus on pelagic seabirds, for example Petrels, Albatrosses & Storm-Petrels of North America (also by Steve Howell), but Oceanic Birds of the World: A Photo Guide is truly comprehensive, covering roughly 270 species of oceanic species using a combination of concise text and more than 2,200 very good quality photographs to help the keen birder on any ocean voyage. Remarkably, the great majority of the photographs were taken by the two authors, both of whom are fanatic seabird experts. In essence, this book is a comprehensive but compact guide to all species of birds that, based on the authors’ very extensive experience, spend most of their lives foraging, feeding, and flying over oceans.

Following a short section explaining how to use the book, which includes a useful glossary, there is a 17-page introduction containing sections on the different types of ocean birds and their taxonomy; tips about identification at sea; information about the use of moult in assisting with identification; where and how to see oceanic birds; and a very short summary of conservation issues. The bulk of the book, 307 pages, are devoted to the species accounts for the “ocean birds” included in the book: the penguins, auks (alcids), diving-petrels, petrels, albatrosses, storm-petrels, tropicbirds, frigatebirds, gannets and boobies, skuas and jaegers, noddies, and phalaropes (2 species). However, note that this book excludes the vast majority of gulls and terns, as well as all species of cormorant and pelicans because they are not considered to be true oceanic species. In comparison, Harrison (1985) included loons (divers), grebes, pelicans, cormorants, ‘sea-ducks’, and all gulls and terns.

The taxonomy used will not be to everyone’s liking because the authors have not followed any particular taxonomy. Rather, the authors note in the Introduction that “the state of seabird taxonomy is still fluid, and we have tried to pick a realistic course through myriad taxonomic papers…”. Their taxonomic decisions are briefly explained in the section “Taxonomy and Types of Oceanic Birds”, citing many genetic, morphological, and biogeographic studies that support their taxonomic approach and decisions. These and other scientific papers mentioned in the book are listed in the References section at the end of the book, where there is also a very useful five-page taxonomic round-up entitled “Recently Described and Provisionally Split Species”.

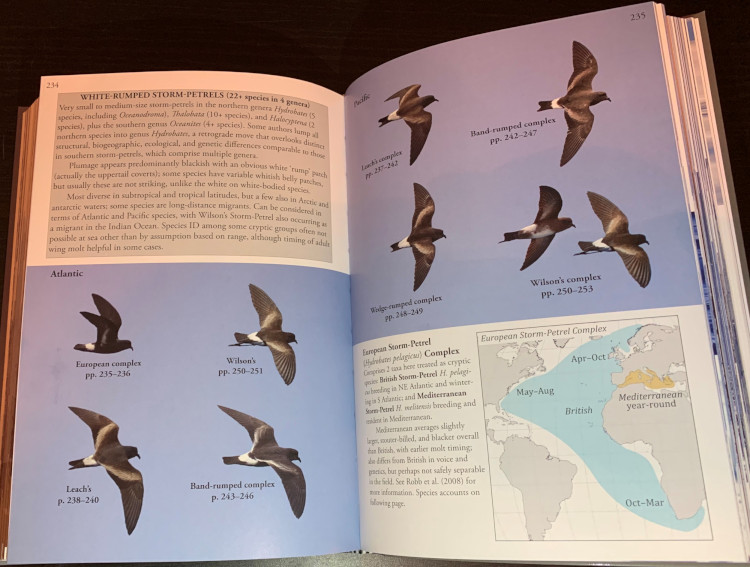

To facilitate the taxonomic approach taken, species (and potential species) are grouped together within species complexes – these comprising groups of what were once considered to be subspecies (races) that the authors believe are better treated as full species. For example, the Manx Shearwater (Puffinus puffinus) Complex, now considered to be three separate species, namely Manx, Yelkouan (P. yelkouan), and Balearic (P. mauretanicus) Shearwaters. Some of these complexes involve highly cryptic taxa, like the Leach’s Storm-Petrel (Hydrobates leucorhous) Complex – composed of Leach’s Storm-Petrel, Townsend’s Storm-Petrel (H. socorroensis), and Ainley’s Storm Petrel (H. cheimomnestes) – or complexes for which the closely related taxa almost certainly include good species but for which the taxonomy is still unresolved: for example, the Band-rumped Storm-Petrel (Thalabata castro) Complex, which is now thought to include as many as ten species, and the Brown Booby (Sula leucogaster) Complex, now thought to contain three species, are all treated in Oceanic Birds as provisional splits but given their own fully-illustrated species accounts.

The species accounts are grouped according to their taxonomy (e.g. Penguins, Petrels, Storm-Petrels). Each of these sections is succinctly introduced with totals for species and genera in that particular taxonomic grouping, with some brief text outlining the important identification characteristics and pointing out which features to focus on in the field. Geographic range, notes on age and sex, feeding behaviour, flight characteristics, nesting behaviour, moulting, and general appearance are all mentioned, where relevant, in this section. The format within each species group, however, varies considerably, which may seem a little confusing at first but makes reasonable sense if you study the book. Indeed, the difficulty in identifying many of the birds included in this book, combined with the subtle variation in format, means that unless you study the book before using it in the field you will not necessarily be able to find what you are looking for as rapidly as you might like to.

For the biggest bird groups, like Petrels (107+ species in 16 genera), the actual species accounts are subdivided further (e.g. under Fulmars and Allies, Gadfly Petrels and Allies), and within these sections the accounts may again be subdivided into groups to assist in identification, such as “Larger White-Bodied Gadfly Petrels”. Within the actual species accounts (usually where unresolved taxonomy exists) some groupings are further divided into the species complexes mentioned above (e.g. “Black-capped Petrel (Pterodroma hasitata) Complex” which includes the White-faced Petrel (P. hasitata) and Black-faced Petrel, which is “formally unnamed”). Where necessary, at the beginning of a section there is a useful photographic table-of-contents that points to the relevant page number.

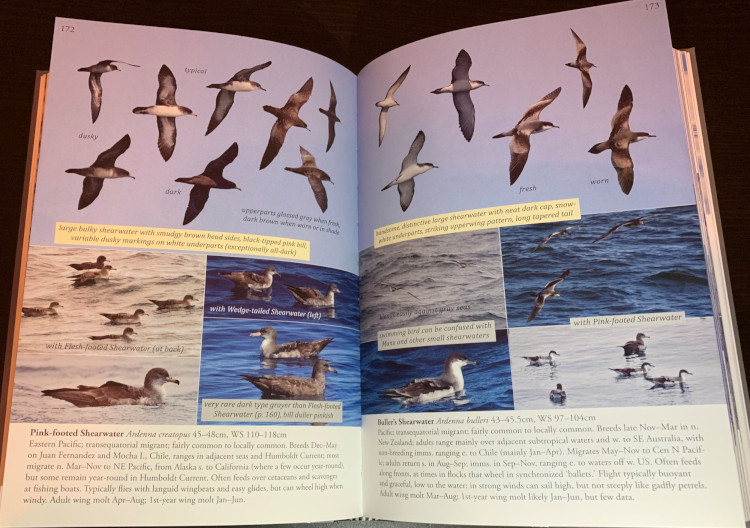

Each species (or provisional species) account contains basic information such as measurements, breeding and distribution ranges, abundance, and relevant identification notes on, for example, flight style, habits, moult sequence, and even vocalizations. Particularly similar species get extra attention, such as “Fea’s Petrel versus Zino’s Petrel” and “Sooty Shearwater versus Short-tailed Shearwater”. There is also a scattering of text-heavy pages that assist in separating some of the more difficult taxa, such as almost a page of text devoted to “Leach’s versus Townsend’s and Ainley’s Storm-Petrels” (three cryptic species, all of which occur off the Californian coast).

The exact distribution of a surprising number of oceanic bird are still poorly-known, although the reasons for this are fairly obvious. Unsurprisingly, then, not all species here have maps, with some ranges just described in the text. Nevertheless, the book includes some 114 colour maps that pinpoint breeding areas, outline normal at-sea distribution, and in some cases indicate the main months of occurrence within different parts of the range. Some of these maps show the distributions of several closely related species. It should always be remembered, however, that oceanic birds can wander out of their mapped ranges and may turn up in unexpected places: for example, I have seen small numbers of individuals from the “White-faced Storm-Petrel (Pelagadroma marina) Complex” in Wallacea, Indonesia, an area that is not mapped in this book for any of the probable six cryptic species within this group, and I once encountered a Pacific Black Noddy (Anous [minutus] minutus some 600km from the sea in New Guinea. An Appendix of five clearly labeled maps shows the location of the various island groups and other regions mentioned in the species accounts. These are very useful, if not essential, for figuring out where species occur when the range is only described in the text.

This is a photo guide, and as such it is the 2,200+ images, with multiple excellent photos for virtually every taxon, that form the most important part of the book. The flight photos have mostly been isolated from their backgrounds so as to be displayed strategically, enabling side-by-side comparisons of look-alike species or plumage variations within species (e.g. dark vs pale phases of many petrels), or for demonstrating aging sequences of notoriously confusing species like the members of the Wandering and Royal Albatross complexes. Underwing and upperwing patterns are clearly shown for all species, even for the majority of those taxa that are only potential species. Thankfully, the photos are labeled directly so there is no need to refer to numbers or some other mechanism to identify what you viewing. Furthermore, key identification features are pointed out with arrows and short statements (such as “white on sides averages more on W. Coast types (see p.239)” for a photo of a Leach’s Storm Petrel (white-rumped) Hydrobates leucorhous). Flight shots and birds sitting on the water or at nesting sites make up the majority of images, but there are a few instances where close-up head shots are used to show the differences between very similar species where features of the bill or eye colour are important, such as in Westland (Procellaria wetlandica) and Parkinson’s (Black) Petrel (P. parkinsoni) and Aukland and Tasmanian Shy Albatrosses (Thalassarche [cauta] steadi and T. [c.] cauta, respectively).

The photographic coverage of the book is extremely impressive, and something that would be impossible to imagine even 15 years ago. There are multiple photos of almost every species, although there are none of Cape Verde Storm Petrel (Thalobata jabejabe) or of the newly described (and Critically Endangered) Atlantic Lesser (or Trindade) Frigatebird (Fregata trinitatus: Olsen 2017). Indeed, for both of these species the authors note that field ID criteria await elucidation, and it maybe that they cannot be safely identified in the field.

Overall, this book is an amazing accomplishment: it is comprehensive yet succinct, both eye-opening and ground-breaking. A brief perusal quickly hammers home just how difficult it is to identify many species of oceanic birds (especially without good quality photos!). The book also highlights how much more there is to learn about the taxonomy of the many cryptic taxa described and illustrated here. Despite the complexity of the subject matter, and the initial panic that might set in when you realize the identification challenges involved, this book is brilliantly organized in a way that will maximize your chances of identifying pelagic birds. It is a moderately-priced bird guide that will prove useful to those who watch birds along the coast, and downright essential for any pelagic trip.

– Reviewed by Frank Lambert

(1 votes, average: 4.00 out of 5)

(1 votes, average: 4.00 out of 5)

Comment