Reviewed by Frank Lambert on September 29th, 2018.

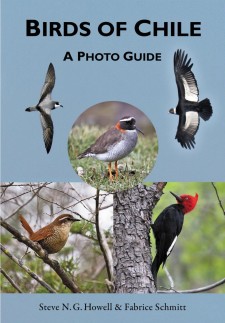

Birds of Chile: A Photo Guide is the first modern-style photographic field guide to the birds of Chile, an increasingly popular destination for world birders. It is described by the publisher as a “cutting-edge photographic field guide”, and I have to agree. I’ve always been sceptical about using photographic bird identification guides, but here is one that exceeds expectations and is surely going to be an essential guide to take on any trip to Chile.

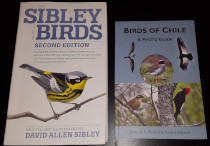

There is of course already an excellent, comprehensive Helm field guide – Birds of Chile (2003) – by Alvaro Jaramillo, that is nicely illustrated by Peter Burke and David Beadle. Both books are the same size (5 3/4″ x 8 1/4″), although the photo guide is thicker and hence slightly heavier. The field guide covers more species but this is partly because it includes the Antarctic peninsula, the Falkland Islands, and South Georgia, as well as vagrants and rarities. The field guide also includes detailed colour maps which are lacking in the photo guide. This is somewhat annoying because one has to keep referring to the maps at the front of the book in order to picture the range of each species from the range description that is given.

The first part of the photo guide is a succinct and very useful section on the geography, habitat, and bird distribution which includes lists of species typically found in the many distinctive zones and habitats to be found in this amazing country, which spans some 2500 miles from severe deserts in the north to evergreen forest and Patagonian steppe in the south (these are illustrated on a map by Jaramillo et al. but not by the photo guide). Comparing the two guides, the photo guide contains the more interesting, and more detailed, overview of bird distribution and their habitats, but it lacks some of the information provided by Jaramillo et al. The photo guide also has a short but useful section on migration.

In the main part of the book, instead of the usual approach of field guides, birds are organized into eight groups: Swimming Waterbirds, Walking Waterbirds, Flying Waterbirds, Gamebirds and Allies, Raptors and Owls, Larger Landbirds, Aerial Landbirds, and Songbirds. This novel approach is likely to be helpful to many birders, and serves to narrow down the range of species to be compared when confronted by something that you can’t immediately identify. It can be a bit confusing, however. For example, Peruvian Thick-knee is in the section of Gamebirds and Allies (along with seedsnipe, tinamous and rheas), whereas I would probably have been inclined to look for it in Walking Waterbirds.

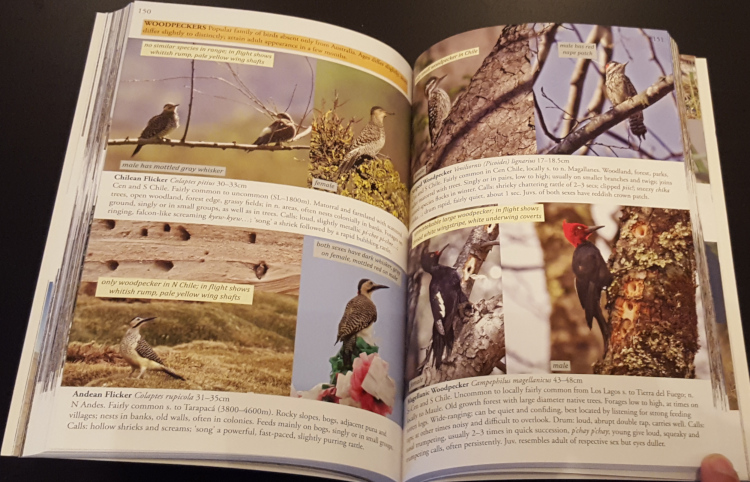

Throughout the book, distinctive groups of birds (e.g. Gulls, Skimmers and Terns; Pigeons and Doves; Earthcreepers; Ground-Tyrants) are introduced with a few lines describing relevant characteristics and behaviour. Each page in main section (190 pages total) generally deals with two species, and there are two or more photos of each. Almost without exception, the photos are of excellent quality and illustrate salient identification features. In particular, seabirds are very well illustrated with up to seven photos for some of the more difficult species (generally those that take many years to become adults). There is a short section of text for each species, highlighting status, distribution (including altitudinal limits), habitat preferences, behaviour, and voice. The most important identification features are provided in highlighted text boxes alongside the photo, with arrows to draw attention to the feature being described. Many photos are of birds in their habitat, further assisting in identification. Overall, this approach is probably more useful than in the many field guides that feature long descriptions of each species, sometimes making it difficult to quickly identify the most important features to look at in the field.

An Appendix, also including a few excellent photos, provides an annotated list of rare and local species that are not in the main part of the book, and hence unlikely to be encountered on the majority of visits to Chile.

The taxonomic approach of the photo guide also differs from that of most field guides (although there are exceptions, for example in recent Lynx Edition field guides to Indonesia and to New Guinea) and this will, I think, prove to be very useful in drawing attention to likely future species. Whilst Jamarillo et al. mentioned and illustrated many taxa that they thought might be split in the future, this did not always jump out at the reader. But in this photo guide these taxa and others stand out very clearly because they have their own “species” accounts. Howell and Schmitt call these taxa “adopted provisional splits”, and in some cases they are already wildly recognised. For example, Cream-winged and Buff-winged Cinclodes (split from Chestnut-winged); Andean and Black-faced Ibis, Patagonian Forest Earthcreeper (split from Scale-throated Earthcreeper), and Peruvian Pipit (split from Yellowish Pipit) are already recognised in the IOC (2018: ver 8.2) and HBW-BirdLife checklists (2014, 2016).

There are also a good number of “Adopted provisional splits” that were elevated to full species by HBW-BirdLife, but not yet by IOC, including Patagonian Silvery Grebe (Podiceps occipitalis) split from Andean Silvery Grebe (P. juninensis), Lesser Rhea split into Puna Rhea (Rhea tarapacensis) and Darwin’s Rhea (R. pennata), White-winged Pigeon (Patagioenas albipennis) split from Spot-winged Pigeon (P. maculosa), Rufescent Flycatcher (Myiophobus rufescens) split from Bran-colored Flycatcher (M. fasciatus), Coal Black Thrush (Turdus anthracinus) split from Chiguanco Thrush (T. chiguanco). Other taxa not split by IOC but tentatively recognised as a full species by HBW-BirdLife (with a highlighted English Name) are American Great Egret (Ardea egretta) split from Great Egret (A. alba), Chilean Lapwing (Vanellus chilensis) split from Cayenne Lapwing (V. cayennensis), Chilean Hawk (Accipiter chilensis) split from Bicolored Hawk (A. bicolor), Austral Wren (Cistothorus hornensis) split from Grass Wren (C. platensis), and Yellow-bridled Finch (Melanodera xanthogramma) and Canary-winged Finch (M. princetoniana) recognised as different species.

Additionally, Howell and Schmitt tentatively split a number of species that are not recognised as such by either IOC or HBW-BirdLife. Hence they split Fuegian Storm Petrel (Oceanites chilensis) from Wilson’s Storm Petrel (O. oceanicus), Austral Turkey Vulture (Cathartes jota) from Turkey Vulture (C. aura), Magellanic Snipe (Gallinago magellanica) from South American Snipe (G. paraguaiae), Hudsonian Whimbrel (Numenius husdonicus) from Whimbrel (N. phaeopus), Western Willet (Tringa inornata) from Eastern Willet (T. semipalmata), Chilean Black Rail (Laterallus salinasi) from other populations of Black Rail (L. jamaicensis), Austral Ringed Kingfisher (Megaceryl stellata) from Ringed Kingfisher (M. torquata), West Andean Swift (Aeronautes parvulus) from Andean Swift (A. andecolus), and recognise both Andean Giant Hummingbird (Patagona peruviana) and Chilean Giant Hummingbirds (P. gigas) (previously one species). Patagonian Miner (Geositta cunicularia), Altiplano (G. frobeni) and Chilean Miners (G. fissirostris) are all split from Common Miner, whilst Band-winged Nightjar (Systellura longirsostris) is also split with three species occurring in Chile: Austral Nightjar (S. bifasciata) South Andean Nightjar (S. atripunctata) and Atacama Nightjar (S. decussata), of which only Atacama Nightjar (Tschudi’s) is recognised by both IOC and HBW, and Austral Nightjar is not recognised in either. Finally, as first suggested in the field guide by Alvarillo, Plain-mantled Tit-Spinetail is tentatively split four ways, none of which are recognised by IOC, although Patagonian (Leptasthenura pallida) and Puna (L. berlepschi) Tit-spinetails are both split by HBW-BirdLife. The other two tit-spinetail adopted splits are Chilean Tit-spinetail (L. berlepschi) and Atacama Tit-spinetail (L. grisescens).

There are also two species not included in Jaramillo et al., both being recently described – Pincoya Storm-petrel (Oceanites pincoyae) and Ticking Doradito (Pseudocolopteryx citreola), although the latter was included in the field guide as Warbling Doradito (P. flaviventris).

Recommendation

Based on the above, I think it is very clear that any serious birder should seriously consider taking both Birds of Chile: A Photo Guide and the older field guide if they are intending to bird in Chile. Additionally, the photo guide will also prove valuable when visiting the adjacent countries of Argentina, Bolivia, and Peru. Whilst the field guide is probably the more essential of the two, the photo guide should be sufficient to identify almost everything one sees well, and could certainly be used on its own. As stated by the publisher, this is a cutting-edge photographic field guide, and an invaluable addition to any birder’s library.

– Reviewed by Frank Lambert

References

del Hoyo, J. and Collar, N.J. 2014. HWB and BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World. Vol 1. Non-passerines. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

del Hoyo, J. and Collar, N.J. 2016. HWB and BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World. Vol 2. Passerines. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

Jaramillo, A. Burke, P. and Beadle, D. 2003. Birds of Chile including the Antarctic Peninsula, the Falkland Islands and South Georgia. Helm Field Guides. London.

Comment