Reviewed by Frank Lambert on November 25th, 2009.

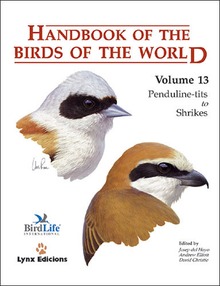

Recent volumes of Handbook of the Birds of the World (hereafter HBW) have kept up to a very high standard in terms of both presentation and content, and HBW 13 is no exception. This volume even includes Togian White-eye Zosterops somadikartai, described only in 2008. The text on the 16 families has been put together by 20 different authors, and the photos, which are again superb, draw on the skills and luck of numerous photographers. Photographs of many rare and little-known species are included, such as White-browed Nuthatch Sitta victoriae from Mt. Victoria, Myanmar, Pygmy Tit Paslatira exilis from Java, Rufous-throated White-eye Madanga ruficollis of the highlands of Buru (Indonesia), Black-ringed White-eye Zosterops anomalus of southwest Sulawesi, Black-eared Miner Manorina melanotis of Australia and Long-bearded Honeyeater Melidectes princeps from the mountains of Papua New Guinea. However, the photograph of New Ireland Friarbird Philemon eichhorni on page 577 is apparently not this species – the photo shows a bird with a distinctive casque at the base of its bill, which this species lacks – according to both the text and painting. Indeed, the photograph may well be a Helmeted Friarbird P. buceroides yorki even though the text states that this photo was taken on New Ireland, where P. eichhorni occurs but P. buceroides is absent. On New Ireland, the friarbird occurs in mostly inaccessible montane forests – I failed to find it in two days of searching in the only easily accessible forest at 800-1,000m, suggesting that it is rare and mainly occurs above this altitude.

HBW 13 covers 595 species in 16 Oscine Passerine families:

- Remizidae (Penduline-tits)

- Aegithalidae (Long-tailed Tits)

- Sittidae (Nuthatches)

- Tichodromidae (Wallcreeper)

- Certhiidae (Treecreepers)

- Rhabdornithidae (Rhabdornis)

- Nectariniidae (Sunbirds)

- Melanocharitidae (Berrypeckers and Longbills)

- Paramythiidae (Painted Berrypeckers)

- Dicaeidae (Flowerpeckers)

- Pardalotidae (Pardalotes)

- Zosteropidae (White-eyes)

- Promeropidae (Sugarbirds)

- Meliphagidae (Honeyeaters)

- Oriolidae (Orioles)

- Laniidae (Shrikes)

With the exception of 7 species (including the Verdin Auriparus flaviceps, presently treated as an aberrant member of the Remizidae but likely to be something else), none of these species are found in the new world, and the families covered give this volume a distinct Old World bias, with good representation from Asia and Africa, as well as from Wallacea, Australasia and the pacific islands.

The forward, by Ian Newton, is a 32 page essay on Bird Migration. Whilst this is a fascinating subject, and the essay well researched and written, I was a little disappointed that virtually all the examples given were of species from the Western Palaearctic and North America or of waterbirds. The inclusion of some of the less widely appreciated aspects of migration, such as that of intra-tropical migration within Africa or South America, or indeed a few paragraphs on the significant number of Austral migrants which escape the southern winter by moving northwards into often very different habitats in the Amazon or Atlantic forests, would have spiced up this essay.

A quick perusal of HBW13 again illustrates the dynamic nature of avian taxonomy and the ever increasing role that studies of DNA and vocalisations is playing in determining species limits. It is also to some extent a reflection of the ease of finding representative vocalisations for even obscure taxa (see, for example, the ever expanding sound collection at xeno-canto), most of which are being contributed by the hundreds of birders who now make sound recordings on their travels. Now that it is possible to make excellent digital recordings on very light equipment and upload and share the recordings on the internet, this trend is only likely to accelerate the process of splitting that is rapidly unfolding in the neotropics, the Orient and elsewhere. Some of these “new” species are rather cryptic and were easily overlooked without access to vocal information, but others, such as Sulphur-billed Nuthatch Sitta oenochlamys of the Philippines probably should have been recognised as good species many years back.

This recent trend in splitting of species, particularly in the Asian region, is well demonstrated by HBW13. For example, when Sibley & Monroe (1990) was published, and even as recently as 1995 (Harrap and Quinn 1996), only six species of Certhia treecreepers and 24 nuthatches were recognised. Now, after careful studies of morphology and vocalisations, there are nine and 27 species respectfully, and future studies of the Spotted Creeper Salpornis spilonotus may result in the splitting of African and Oriental taxa. Species that had not been “discovered” when I first visited Asia, such as Neglected Nuthatch Sitta neglecta, Przwalski’s Nuthatch S. przewalski and Hodgeson’s Treecreeper Certhia tinquanensis now leap out of the pages as I thumb through this informative book.

Other examples of recent Oriental region splits include Grey-throated Sunbird Anthreptes griseigularis, now a Philippine endemic, Vigors’s Sunbird Aethopyga ignicauda of western India and Grey Friarbird Philemon kisserensis of small islets to the east of East Timor. Apart from splits, there have been a significant amount of moving taxa between families in recent times. In this volume, two good examples are of the Bonin White-eye Apalopteron familiare, which was previously considered to be a honeyeater, and McGregor’s Honeyeater Macgregoria pulcher, previously considered to be a bird-of-paradise (Paradisaeidae).

It seems a pity that nobody has yet had time to tackle the question of species limits of Black-naped Oriole Oriolus chinensis, which according to HBW has 20 subspecies, with a breeding distribution from SE Russia and China through Southeast Asia and the Philippines to most of the Indonesian archipelago; the migratory northern race diffusus winters mainly in the Indian subcontinent and Southeast Asia. Whilst many of the subspecies are very similar, and indeed also similar to Slender-billed Oriole O. tenuirostris, some are very different and there are very likely some that represent good species. One excellent example of this is provided by the taxon melanistictus of the Talaud islands (Indonesia), illustrated on Plate 55. This is just one of what may turn out to be several orioles that should be recognised as island endemics.

Despite all the evidence of the trend towards splitting, HBW sometimes takes a more conservative approach to taxonomy, as can be seen within the flowerpeckers. Thick-billed Flowerpecker Dicaeum agile, for example, include the Philippine forms that are sometimes treated as a separate species Striped Flowerpecker D. aeruginosum (e.g., by Inskipp et al. 1996 and Kennedy et al. 2000), whilst Plain Flowerpecker D. concolor includes the Andaman taxon virescens, which Rasmussen and Anderton (2005) treat as an Andaman endemic – this taxon is “markedly morphologically and vocally distinct from Plain Flowerpecker, which may not be its closest relative”. Rasmussen and Anderton (2005) also consider the western Indian form to be a good species, Nilgiri Flowerpecker D. concolor (whilst Plain Flowerpecker is treated as D. minullum). Personally, I would trust Rasmussens’ judgement on these particular taxonomic decisions rather than those taken by HBW.

The spiderhunters of the genus Arachnothera are probably another group where species limits are yet to be fully determined. “Everett’s Spiderhunter A. everetti”, which was considered to be a subspecies of Grey-breasted Spiderhunter A. affinis (“a race with more heavily streaked breast whose status is not clear”) by Smythies (1981) but later recognised as a good species by Sibley & Monroe (1990) and Inskipp et al. (1996), is now back to being a subspecies of A. affinis – which is now Streaky-breasted Spiderhunter – that is found only in the foothills and lower montane forests of Borneo and in Java and Bali. On the other hand, Grey-breasted Spiderhunter is now A. modesta, a species found in the lowlands of peninsular Malaysia, Sumatra and at scattered localities in the lowlands and hills of Borneo. Yes, taxonomy can be confusing!

For keen world birders, this is a very important volume to possess since it includes illustrations of all the white-eyes (98 species), a group that includes many similar taxa, as well as those of another large (mainly Australasian) family the honeyeaters (175 species): neither of these groups have been covered elsewhere in any recent monograph. And whilst some readers may have the impression that white-eyes are relatively uninteresting or boring, a quick glance at Plate 36 may change your mind. It is a diverse group of birds with some stunningly plumaged species! HBW is undoubtedly one of the most important references for any keen birder or ornithologist to own, and I for one look forward to the last three of the 16 volumes. When Volume 16 is published in late 2011, it will complete the first work to describe and portray each species of any entire Class of the Animal Kingdom (with the obvious exception of some of those species that have been described during the publication period).

– Reviewed by Frank Lambert

You can order this book through the publisher’s website. Alternatively, those in the US might prefer to order from Buteo Books to save on shipping charges.

Resources used:

- Harrap, S. and Quinn, D. 1996. Tits, Nuthatches and Treecreepers. Christopher Helm and A.C. Black, London.

- Inskipp, T. Lindsey, N and Duckworth, W. 1996. An Annotated Checklist of the Birds of the Oriental Region. Oriental Bird Club.

- Kennedy, R.S. Gonzales, P.C., Dickinson, E.C., Miranda, H.C. and Fisher, T.H. A Guide to the Birds of the Philippines. 2000. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Rasmussen, P.C. & Anderton, J.C. 2005 Birds of South Asia: the Ripley guide. Barcelona: Lynx Edicions.

- Sibley, C.G. and Monroe, B. 1990. Distribution and Taxonomy of Birds of the World. Yale University Press, Newhaven and London.

- Smythies, B.E. 1981. The Birds of Borneo. The Malayan Nature Society and The Sabah Society, Kuala Lumpur and Kota Kinabalu.

Disclosure: I get a small commission for purchases made through links in this post.

Comment