Reviewed by Grant McCreary on July 11th, 2015.

There are many ways to identify a bird – by color, by sound, even by behavior. But birding by impression? That doesn’t sound very exact. And yet, that is what experienced birders do all the time. They don’t so much identify birds as recognize them. This recognition is achieved through a combination of what the bird looks like (both color and, especially, shape and structure), how it behaves, and where it is (both range and habitat). These combine to form an overall impression that can be as definitive as checking off every traditional, plumage-based field mark.

So how does birding by impression (BBI) work? Karlson and Rosslet tell us how in Peterson Reference Guide to Birding by Impression. According to our authors:

BBI includes an initial evaluation of birds that uses several key unchanging characteristics, such as a bird’s size, body shape, structural features, and behavior.

The first step in understanding what BBI is and how to put it into practice is to read the 18-page introduction. Seriously, read this first. To get the most out of BBI, you need to understand the basics and have an intentional mindset. The intro will help with both and give you the foundation you’ll need once you move on to the family accounts.

The bulk of Birding by Impression is a look at bird groups through the BBI lens. Most of these groups are at the family level (waterfowl, flycatchers, warblers, etc.). Others have been combined where it makes sense, such as the longspurs with sparrows and the nuthatches and Brown Creeper with woodpeckers. Each of these group accounts include the following sections.

(Note: When I say here that something is or is not useful, I’m not commenting on the value of the information itself, which is considerable. Indeed, these are things that birders will need to know. Rather, it’s a judgment whether it adds value to this particular book. That is, would you want to buy this book to get this information?)

- Physical Profile – The “unchanging features” of the group. This is a short description of the group in general. It may help in differentiating one group from another, but this is the sort of information that birders should be able to easily ascertain from a good field guide. I would say this section is not useful.

- Look-alike Birds – Compares the group to other, similar ones. The warblers, for instance, are contrasted against vireos and kinglets. Some get more specific, like the sparrow account, which are compared against Red-winged Blackbird, Indigo Bunting, Bobolink, House Finch, and House Sparrow. While some field guides, particularly The Sibley Guide, include similar information, this section would be useful to beginning and improving birders.

- Birding by Impression Information

- Size – A measurement is given for the smallest and largest species within the group, and each is compared against another, hopefully familiar, bird. The comparison is nice, because it gives context to the number. If you’re not familiar with the American Dipper, for example, finding that it is similar in size to a Wood Thrush is much more meaningful than having the measurement alone. Still, there’s not much to help you differentiate between birds within the group, so I would say that this is somewhat useful.

- Structural Features – Describes the overall shape. Unless the group only has a few members, it doesn’t get down to species, but rather focuses at the genus level. As the authors say, “It is better to initially familiarize yourself with the typical structural features of each genus than to try to remember all the various structural features of each species.” Useful for beginners.

- Behavior – This is an area not always covered well by field guides. Again, it focuses more on genera than individual species, but this is useful.

- Plumage Patterns and General Coloration – A very general overview of the group’s plumage. This is so generic, and something that is easily ascertained from flipping through a field guide, that I think it’s not useful.

- Habitat Use – Like behavior, this is very helpful information that some field guides may not include. Useful.

- Vocalizations – Like the plumage patterns section, this is too general in most cases. Vocalizations are usually covered in field guides, but this is one area where it’s helpful to have multiple sources because sounds are so difficult to describe well. Possibly useful.

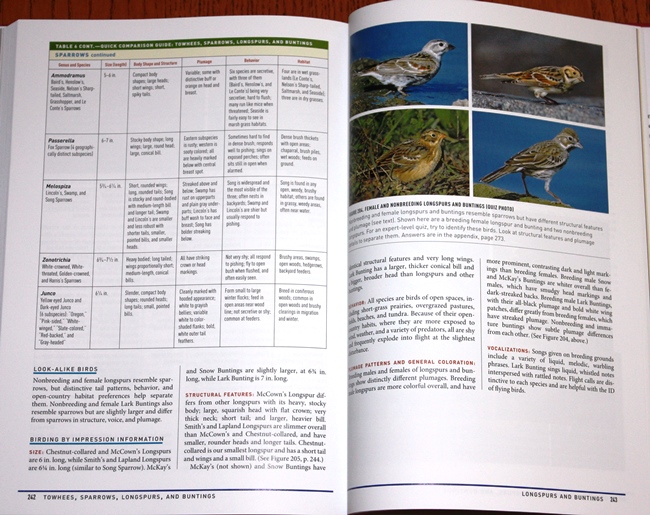

Some group accounts also include an additional section on viewing and/or finding these birds, which could be very useful for beginners. Additionally, there are “Quick Comparison Guides” for six of the groups (raptors, terns, hummingbirds, flycatchers, warblers, and sparrows). These are tables that compare species or genera against a variety of relevant characteristics. Some of these tables, like the one for raptors, still won’t help much with species identification, but should be of assistance to those who need help differentiating accipiters from buteos and kites from falcons. Overall, these guides can be a valuable tool to learn what to look for on these birds, especially if used in conjunction with field guides so that you can match the text here to pictures.

It should be clear from the preceding that these accounts are very broad in scope, dealing with the birds in general, with little species-level specifics. I may be missing something here, but I fail to see the value in much of the information. For example, regarding raptors we are told: “Some buteos have larger heads and bills than others, while some have longer wings that taper toward the tip, which are helpful ID features in flying birds.” This could be very beneficial information, but only when elaborated upon. Which species have the larger heads? The tapered wings? The book doesn’t say.

The final part of the group accounts does get more specific with a comparison of similar species in regard to BBI and non-BBI features. There is some very useful information here, including some pointers that I haven’t come across before. One prominent example, at least for me, was the Laughing vs Franklin’s Gull comparison. I’ve been wanting to find a Franklin’s Gull in Georgia for quite some time (they’re annual, but rare and far, far outnumbered by their similar-looking cousin). But I’ve had issues with one traditional field mark – the darker head of a non-breeding Franklin’s, with more prominent white eye-brows. I’ve found Laughing Gulls to be so variable, with some having heads as dark as Franklin’s are supposed to have. According to Karlson and Rosselet, this is especially an issue from January onward, when Laughing Gulls are molting in their dark breeding head feathers. This is very helpful, as I now know to pay much closer attention to this between, say, October and January. They also point out a new field mark (well, new to me) in the Franklin’s more extensive white between the gray back and black primaries.

Male Cooper’s vs female Sharp-shinned Hawk, Antillean vs Common Nighthawk, Birding by Impression covers some very difficult identification puzzles. However, I was surprised that some confusing species pairs are not included. It has LeConte’s vs Nelson’s Sparrow, but not Saltmarsh vs Nelson’s, a pair that trips me up on the coast in winter when you’re lucky to get just a brief glimpse of one of these birds. But maybe that’s just me. Inarguably difficult, though, are Empidonax flycatchers. The only pair of these little devils treated in detail are Willow and Alder. You could pick out virtually any two birds from this group and they would be worthy of attention. But at the very least we need the “Western” Flycatchers (Pacific-slope and Cordilleran).

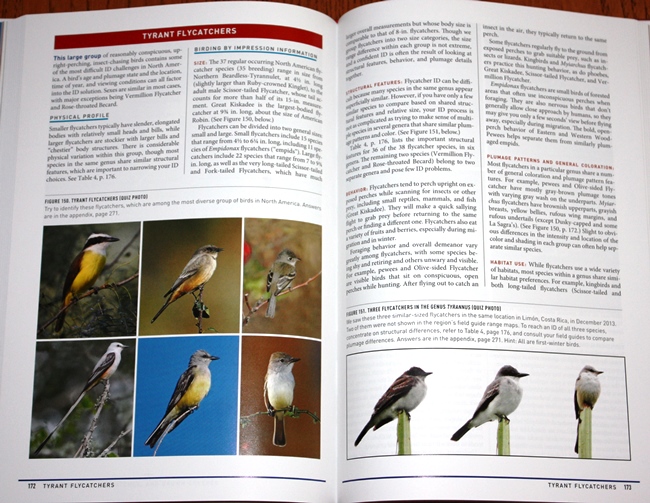

Photographs are an integral part of Birding by Impression, even more so than most identification guides. The photos of similar species are grouped together, with the birds in roughly the same position and posture to facilitate comparison. The best thing, though, are the captions. Or the lack of them, for the vast majority do not even identify the birds. These are “quiz photos”, designed to get you to look critically at the images and apply the information presented in the text. The answers, often with helpful pointers, are contained in an appendix. But don’t turn back there too quickly. Instead, as the authors suggest, look at the photos first, noting differences between the birds. Then read the text and see if you can identify them. Finally, check the answer in the back.

I love these quizzes, and have since Karlson and his co-authors did something similar in The Shorebird Guide. They are very effective in demonstrating some of the traits mentioned by the authors, especially the structural features. BBI requires experience, and critically examining these photos is the first step. A good next step that will help you remember what to look for is to practice on other sources. Open up a field guide and see if you can pick out the features mentioned here (The Crossley ID Guide works particularly well for this).

There are a few minor negatives related to the photos that should be mentioned. A relatively small number of species are shown, especially for an identification guide. And some of the pictures are pretty small. Strangely, the biggest drawback may be color! The Advance Reading Copy of this book (a pre-publication version sometimes sent to reviewers) was identical to the final published version, except that it was printed in black-and-white. I found that without plumage color to distract me, it was easier to concentrate on the plumage patterns and structural details. But I realize that going without color is unlikely to happen due to the economic realities of publishing (it’s likely that most potential buyers would immediately put the book back on the shelf if they opened it to find predominantly black-and-white photographs).

Recommendation

So, is birding by impression worth it? If you’re referring to the practice, then most definitely. It has the potential to improve anyone’s birding skills. As Karlson and Rosslet write:

BBI allows new and casual birders to build lasting ID skills that don’t require constant referencing of field guides, and gives advanced birders an opportunity to take their birding skills to new levels of proficiency and enjoyment. In both cases, the end result of this approach is truly knowing a bird rather than just identifying it.

But Birding by Impression, the book? The answer isn’t as clear. I was really looking forward to it, but was disappointed. I was hoping for more information at the species identification level. But if I look past that and focus on what is here, then I have to admit that it could still be valuable, especially to beginning and intermediate birders (or “improvers”, as an article I recently read put it). It does have some good pointers for separating difficult-to-ID birds. But the main benefit is that throughout the book, and especially in the introduction, the authors model a different way of looking at birds. This filter, so to speak, is built up with experience. Birding by Impression is no substitute for experience (which the authors acknowledge), but it does provide a foundation that you can use to start building that filter based upon your experiences, and to do so much quicker than you otherwise would have been able to.

Disclosure: I get a small commission for purchases made through links in this post.

Buy from NHBS

(based in the U.K.)

Disclosure: The item reviewed here was a complementary review copy provided by the publisher. But the opinion expressed here is my own, it has not been influenced in any way.

Comment